The Mushroom at the End of the World by Ana Lowenhaupt Tsing

Gunnar’s Daughter by Sigrid Undset

Pig Earth by John Berger

Owlish by Dorothy Tse

Dialectic of Enlightenment by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer

Ædnan by Linnea Axelsson

By Night in Chile by Roberto Bolaño

Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar

Ulysses by James Joyce

Family Lexicon by Natalia Ginzburg

Reading the Room by Paul Yamazaki

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen

Too High and Too Steep by David B. Williams

Slow Down: A Degrowth Manifesto by Kohei Saito

Paterson by William Carlos Williams

Toad by Katherine Dunn

The Lines That Make Us by Nathan Vass

The Missing Pieces by Henri Lefebvre

Living by Henry Green

Shopkeeping by Peter Miller

Towns and Buildings by Eiler Steen Rasmussen

The Death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs

Mural by Mahmoud Darwish

Middlemarch by George Eliot

Grand Hotel Europa by Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer

A Man of Two Faces by Viet Thanh Nguyen

The Situationist City by Simon Sadler

N by E by Rockwell Kent

Aiiieeeee! An Anthology of Asian American Writers

The Revolution of 1956-1939 in Palestine by Ghassan Kanafani

Outside the Outside by Matt Hern

Oblique Drawings by Massimo Scolari

Faraway the Southern Sky by Joseph Andras

Post Captain by Patrick O’Brian

Pnin by Vladimir Nabokov

About Looking by John Berger

Abstraction and Architecture by Pier Vittorio Aureli

The Interpretation of Dreams by Sigmund Freud

The Tattered Cloak and Other Stories by Nina Berberova

Dialectics of Seeing by Susan Buck Morss

Walking in Berlin by Franz Hessel

41.5 Shuna’s Journey by Hayao Miyazaki

Seven Days in June by Tia Williams

I Hotel by Karen Tei Yamashita

San Francisco: A Map of Perceptions by Andrea Ponzi

The Black Jacobins by C.L.R. James

Howl and Other Poems by Allen Ginsberg

The Idea of Communism by Tariq Ali

Enter Ghost by Isabella Hammad

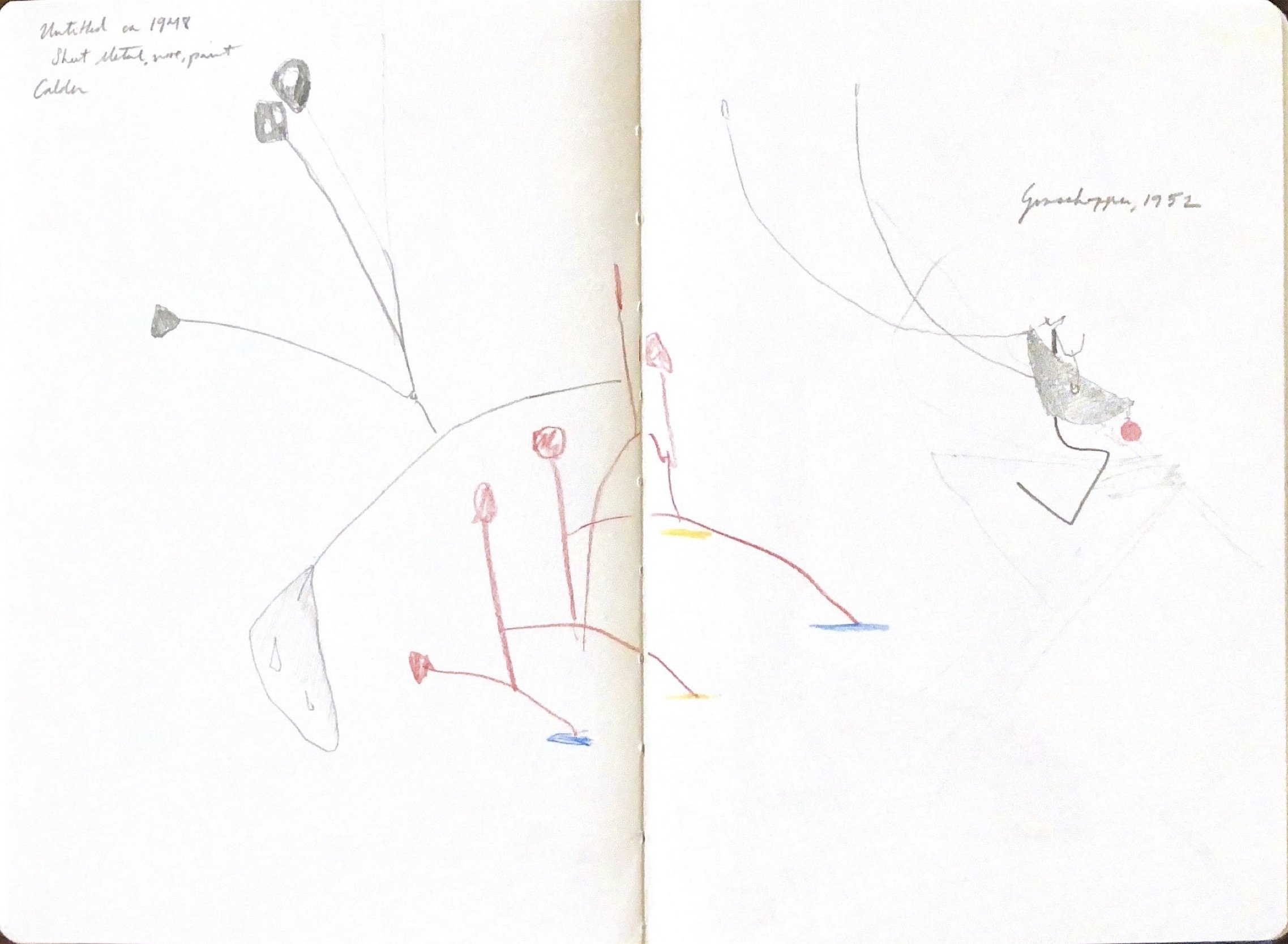

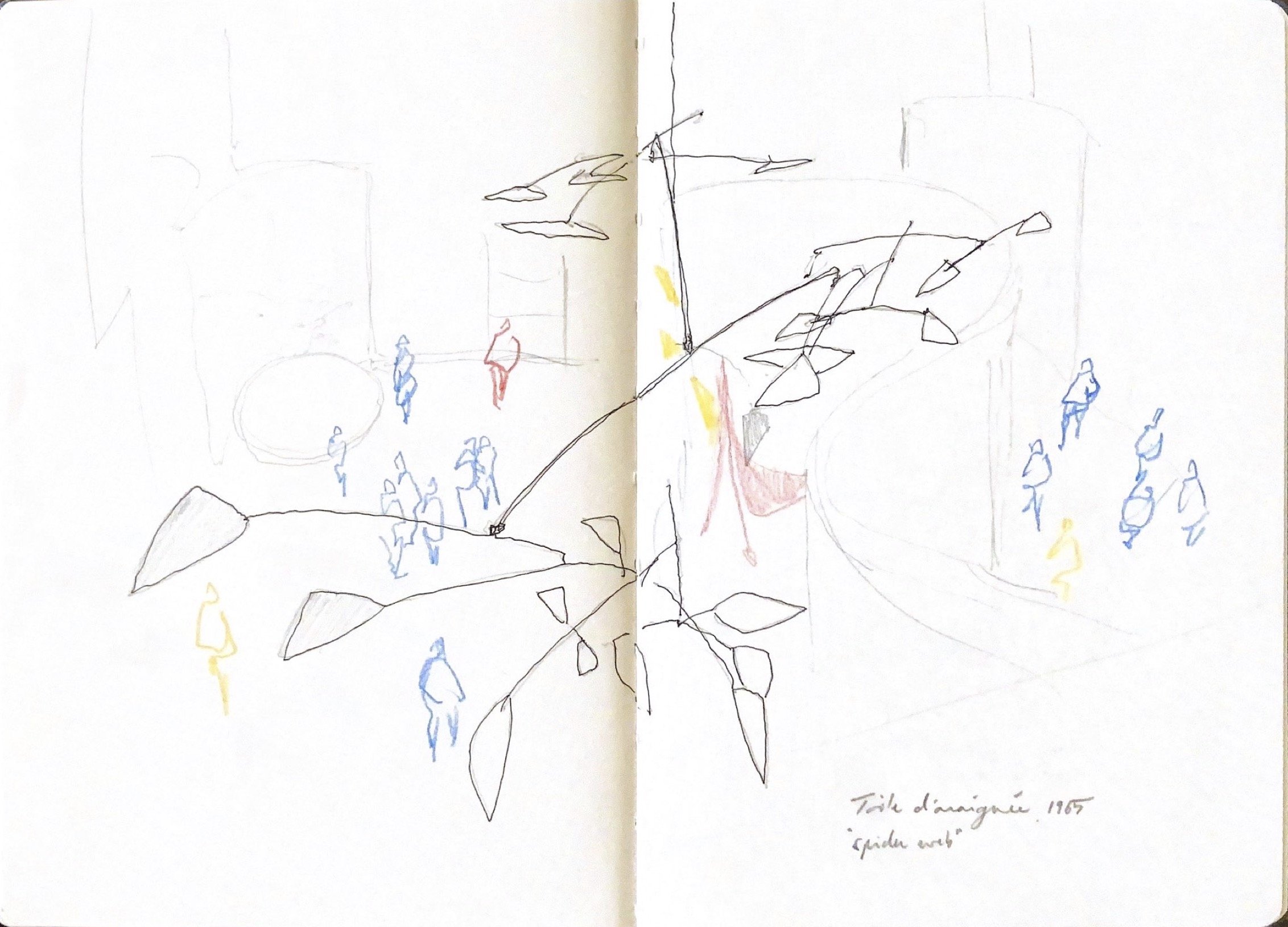

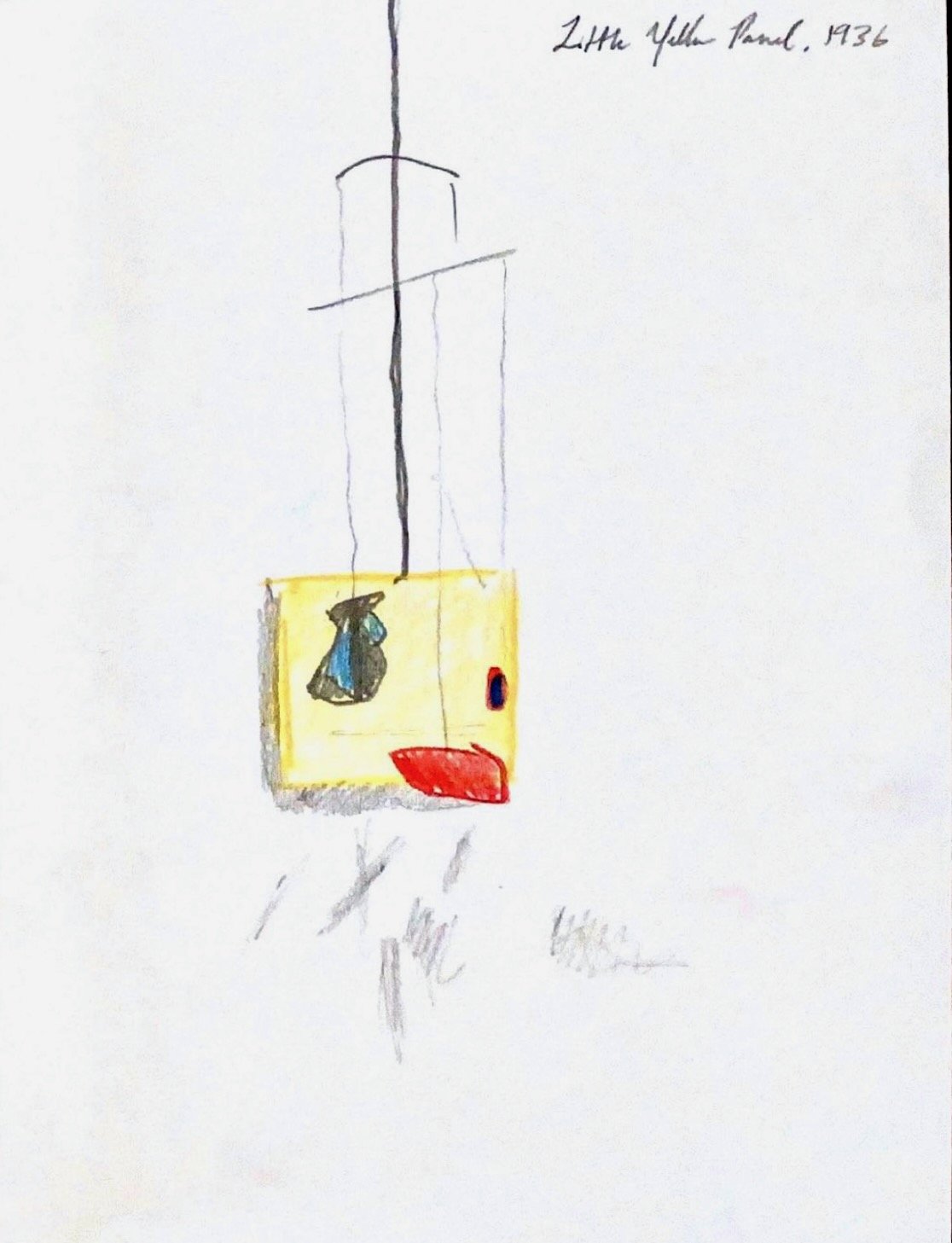

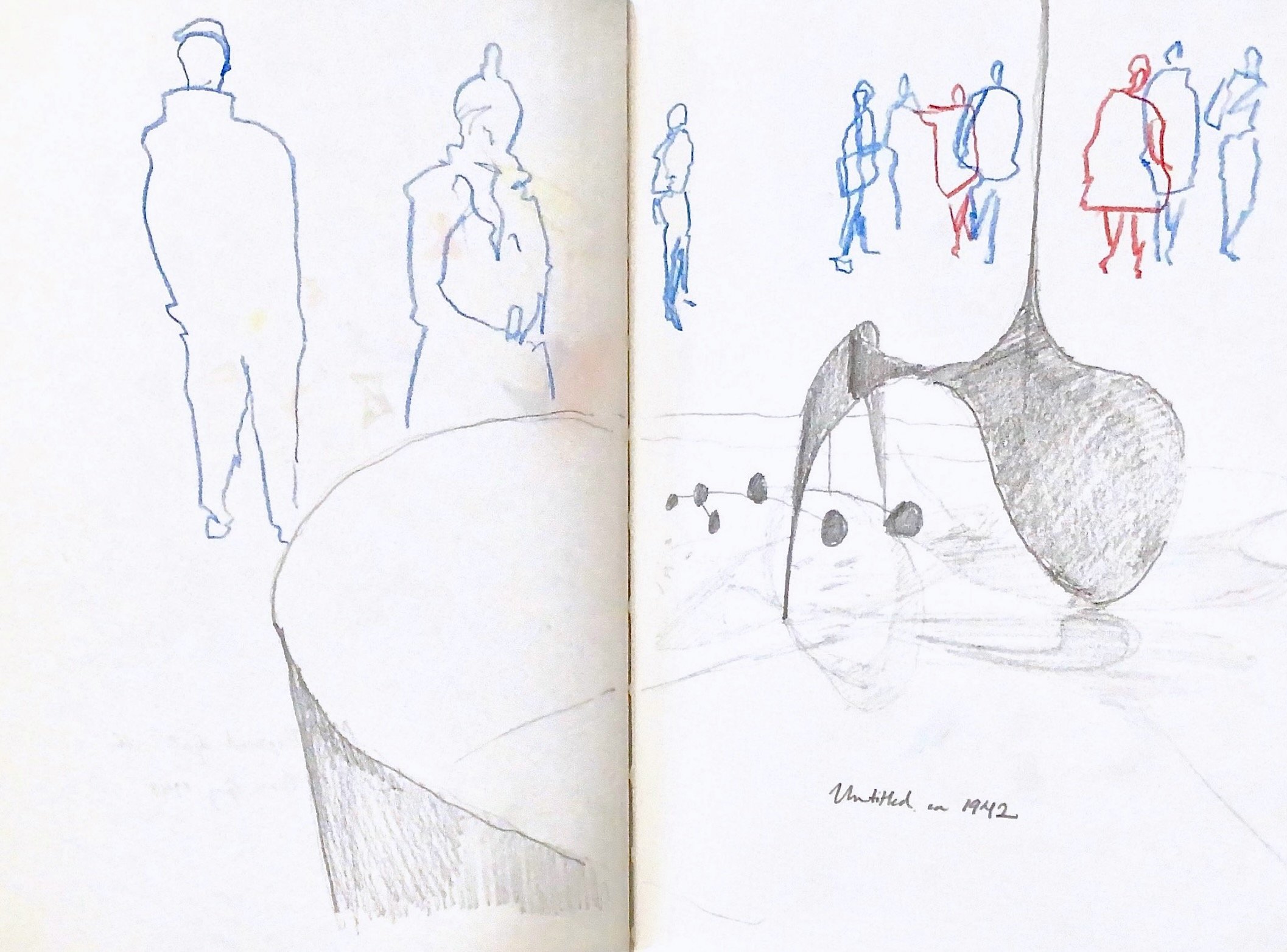

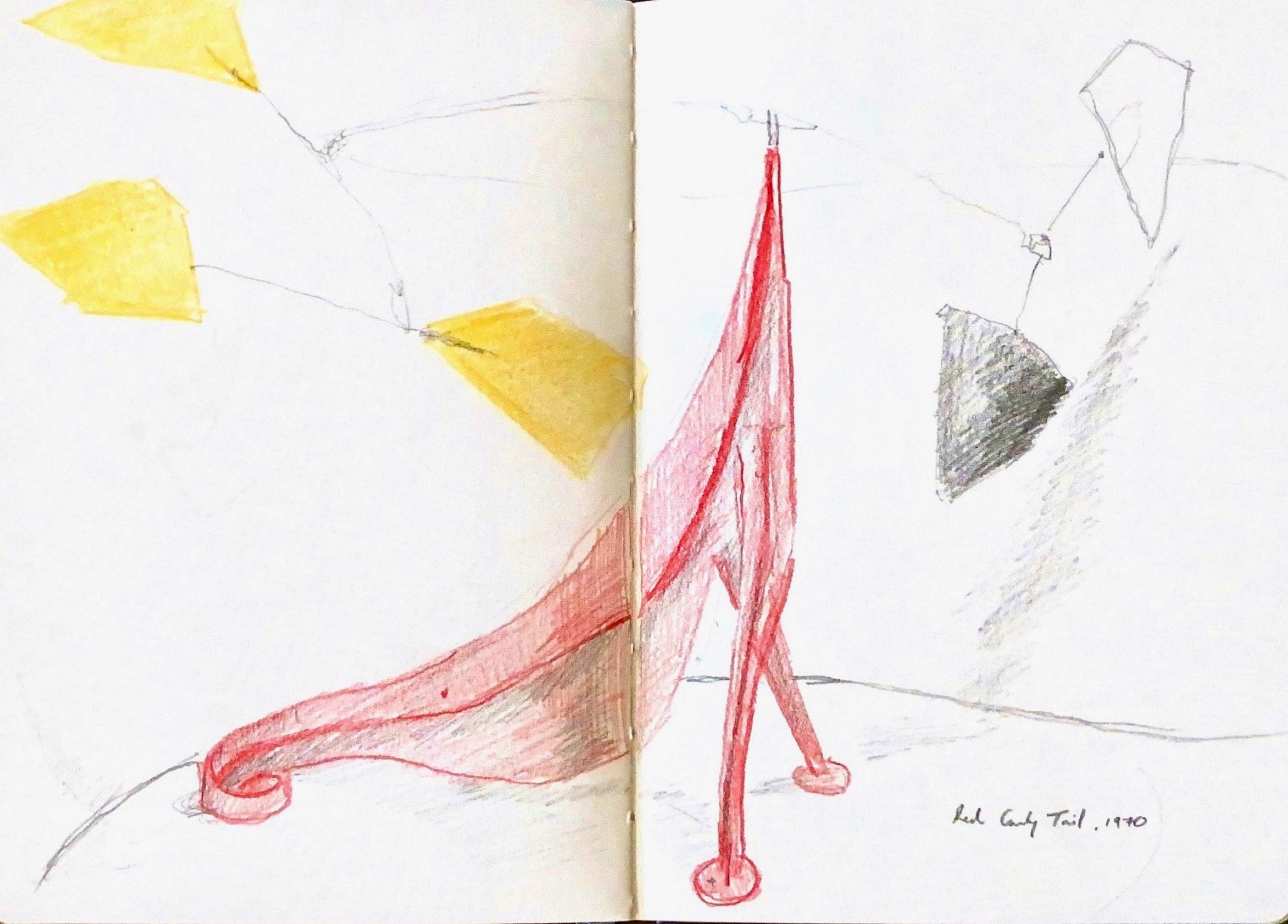

Calder: Mobiles made immobile

Movement. Sequence. Passing. Alexander Calder’s mobiles and stabiles (sculptures that don’t move) are a reply to that famous paradoxical question of Zeno: How is movement possible?

In order for anything to reach a given point, it can be deduced that it must travel at least half that distance. However, in order to travel half that distance, it must travel half of half that distance, ad infinitum, ad nauseam. And yet, movement is possible, we see it, we observe it, or is it simply an illusion? The concept of infinity too incomprehensible a reality that our brains soothe us with the fiction of motion.

Art in motion, or art at rest? Imperceptibly moving or perceptibly still? I see people moving around a stabile, and I see mobiles moving in front of stationary people. My pencil travels across the paper, making marks on the page. Do my drawings move? For my pencil to travel from point A to B it must travel to halfway point C. For my pencil to reach point C (traveling from point A) it must travel to halfway point D.

We take for granted the passage of time, the relation of cause to effect. As the object changes form before our eyes, we recognize it as the same object not something completely new. But the shifting form allows us to see new things. What was once imperceptible is now perceivable. As we walk in circles around the stabile, our understanding changes.

I attempt to document my thinking on paper. Rendering a moment of perception, or rather a series of moments, the passage of time, my pencil, and the objects in the pages of my sketchbook.

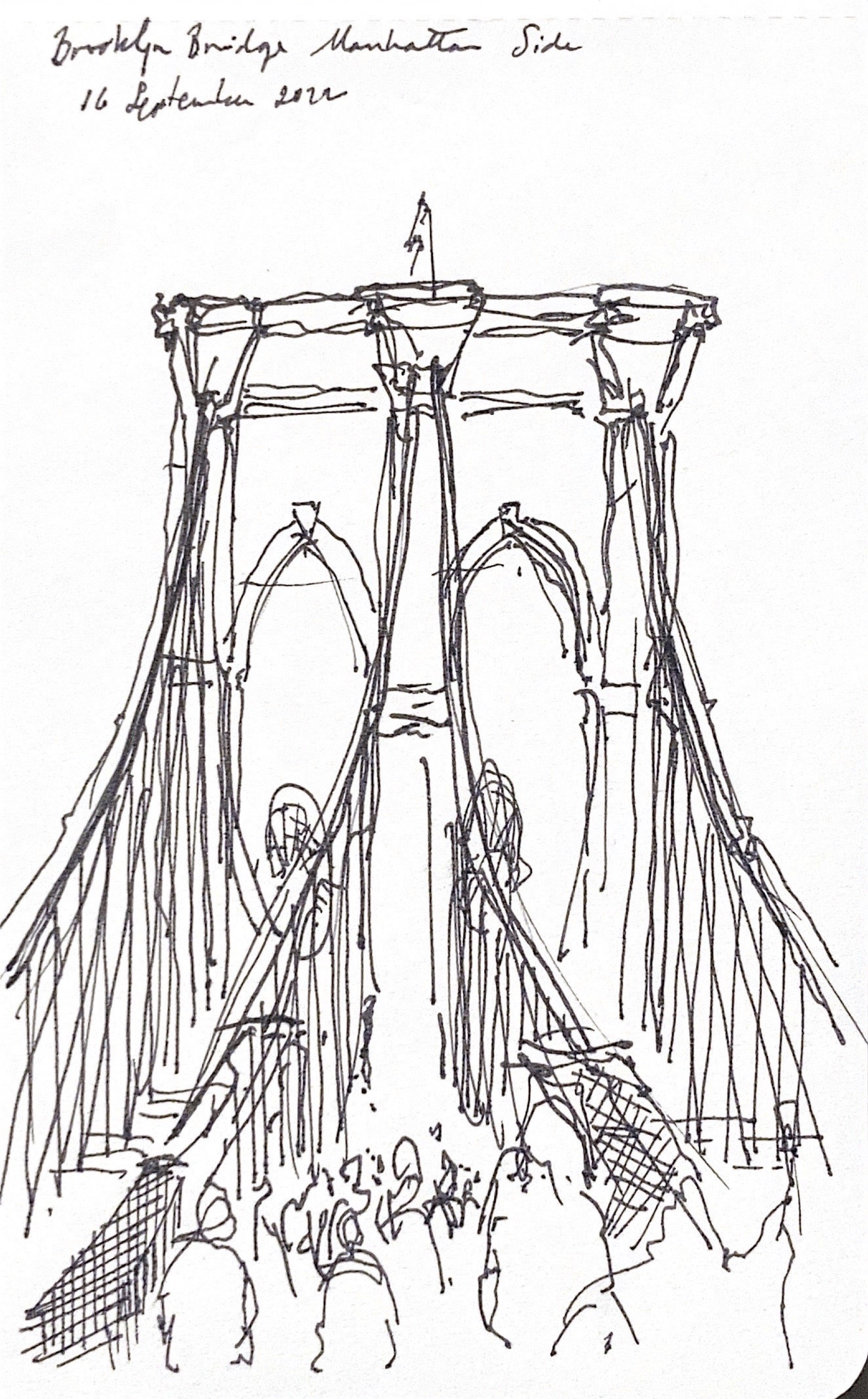

Three Full Days in New York

September 2022

I run the risk of romanticizing a city. And cities are not to be romanticized. They are collections of moments and relations; living breathing beings with organs and circulatory systems. They are places where people live. I am but a guest with the luxury of leaving and returning to my own city. The built environment is not my own so I treat it with a certain reverence. I wipe my shoes on the metaphorical doormat of JFK airport as I arrive. But this is not a temple, it is a collective construction of millions of individuals, thousands of communities; all interconnected with one another. A place where people work, eat, sleep, argue, grow old, learn, pay rent, read, and create. New York is already an institution, a collective ideal. It does not require another endnote of worshipful praise from me. So what is a visitor to do for three days? Despite my brief stay, how has the city shaped me and, how have I shaped it?

A trip is like a museum visit except I play both the role of curator and visitor. As curator, I decide the sights like an exhibit. As visitor, I follow the path laid out for me. I might feel as though I am “wandering” but the experience is tailored to me. What is an “authentic” experience? Tourist, traveler, visitor; what is the difference?

Seattle -> Airport -> Airplane -> Airport -> New York City

Travel itself, is mediated by nowhere spaces. We try to make these transitory moments as seamless as possible despite the monumental number of disruptions and annoyances that we encounter. Other people, going through the exact same experience as us, itching to get to point B. We distract ourselves from these moments in transit. Movies, music, books, sleep, snacks, shopping; everything but the awareness of the act of travel itself. The modern airport is a glorified shopping mall.

With flying, however, there is an added level of strangeness. We are packed like sardines into a flying metal cylinder with wings, launched at high speed into the sky, then miraculously soar at 30,000 feet above the clouds for hours, then glide back to the surface. Our legs fall asleep, we squirm, we grumble, and we clench our jaws.

***

Three full days in New York; the weather is warm and sunny, mornings are cool and evenings are pleasant, perfect weather for documenting travels in ink, watercolor, and light. I bring an Ilford Sprite 35mm camera, a small pocket sketchbook, and a larger 225x500mm sketchbook.

With winds in our favor, we land at JFK an hour early. After relearning the subway system, we arrive at my cousin’s apartment still recovering from travel fatigue, and order pizza for dinner. George, my friend since the third grade who has been living in New York since college joins us. It has been over two years since I saw them last after my original plan to visit in the spring of 2020 was canceled. Our travel adrenaline is beginning to set in. I want to dive in head first, not even remembering just how wide and deep of a pool this city is. It is Sam’s first time, and I can’t wait to share with her a city I have longed to return to since I first visited. We drink, we eat someone else’s pizza that was accidentally delivered to us, we eat more pizza, and eventually retire to bed anxious for tomorrow to begin.

***

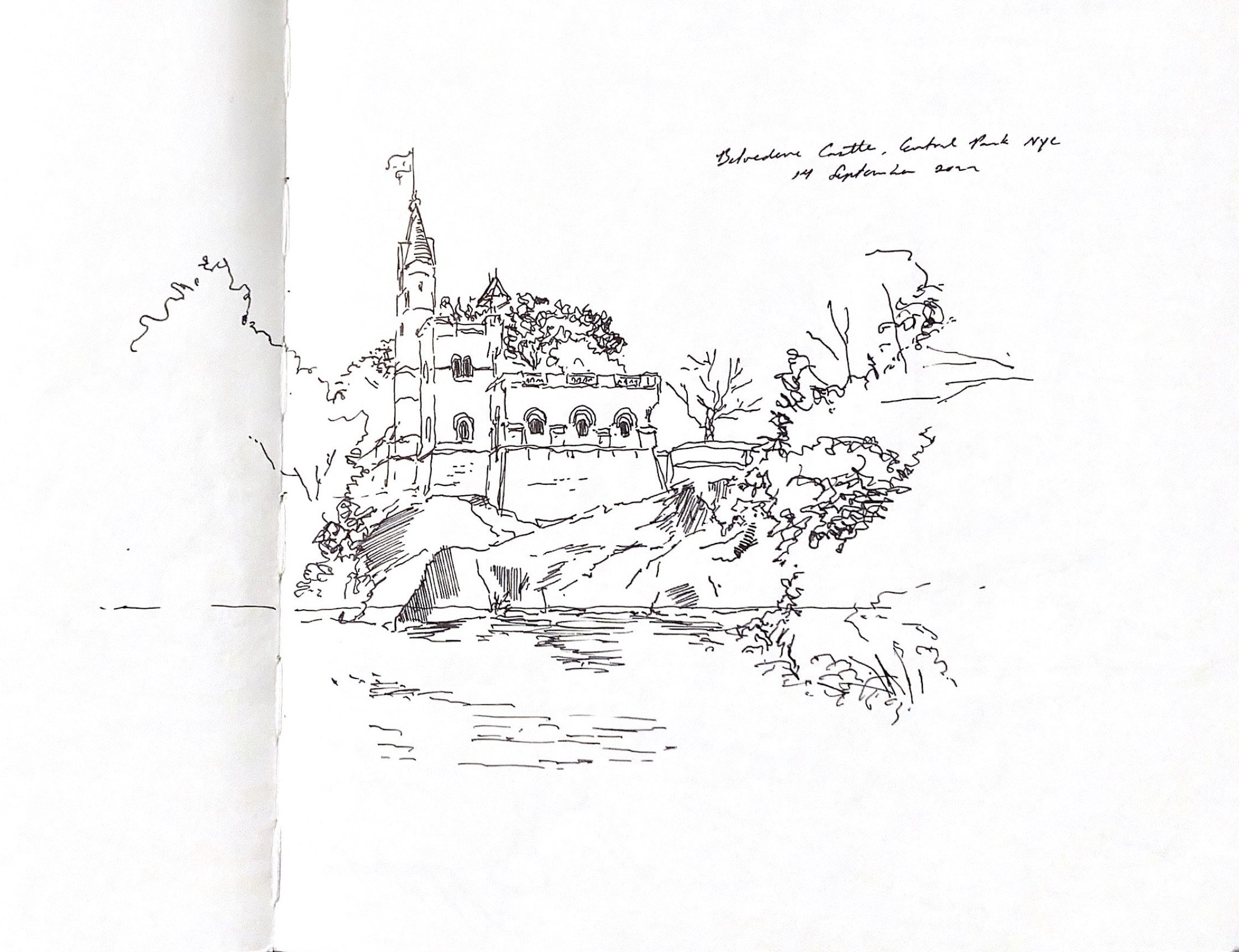

Central Park is first. The F train takes us from Park Slopes to 57th Street. Manhattan greets visitors like a slap in the face when you first emerge from the subway. We dodge horse carriages and tour guides as we enter the park. Olmstead has designed what could be best described as a 19th-century Disneyland. An idealized wilderness, Central Park is a curated collection of lawns, forests, bridges, twisting and tangled paths, and a castle. We stop at the Bow Bridge where I start my first watercolor of the trip. The blue sky is juxtaposed with the murky green of the water. The San Remo towers stand tall above the dense treeline. Monoliths of iron, stone, and glass stretch up as if to remind those inside this green sanctuary that the concrete jungle awaits their return. As we stroll on, it is like being in a Grimm fairytale story. I draw the Belvedere Castle (the original Anaheim Sleeping Beauty palace).

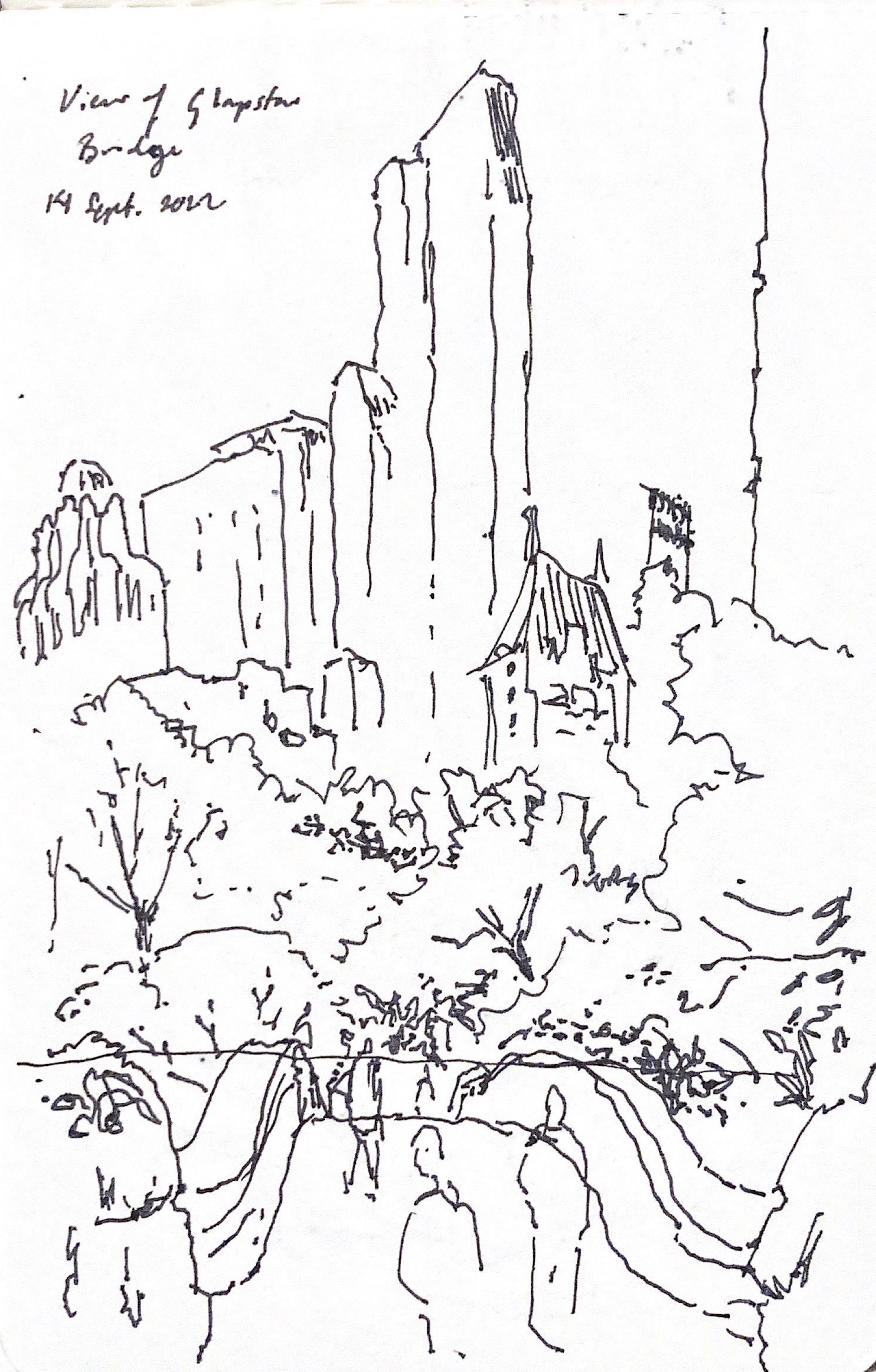

Passing ponds and lakes, traversing through miniature forests, and pondering statues, we crisscross our way to the Glapstow Bridge to meet George. We walk from Central Park to Lincoln Center and spend some time wandering around the plaza. The simple and imposing forms stand tall above us, modernist geometric behemoths. From here we drag our feet through Hell’s Kitchen to grab some sandwiches. We realize we are not far from Bryant Park and the New York Public Library and on the way, we pass through Times Square.

It is a war zone for attention seekers.

People are bombarded with advertisements that last no longer than 30 seconds on repeat. The people, the ads, the gimmicks, and the performances of both. Eventually, we are overwhelmed and the spectacle is no longer interesting; we continue to the library.

The main branch of the New York Public Library is a cathedral of a building. Staircases zig-zag their way between levels, special collections rooms quietly guard the treasures within them, and footsteps echo down the marble halls.

To get into the Rose Reading Room we say we have “study materials”. We brought books and a newspaper with us on this trip, which is good enough for the guard who is interrogating people wanting to gain entry. We choose a few chairs at a long solid wood table that spans half the width of the room. I sit down in spot #127 and set to work.

The sheer magnitude of this space makes one feel small, but not unimportant. There is a quiet joy in being in a space in which 636 people—be they reading, writing, or in my case, drawing—feel a collective spirit. A library is one of the few remaining spaces in our society in which no one is expected to buy anything. Instead, we are genuinely asked to be curious. The library asks us to pause and to think for ourselves, away from the incessant pleading and begging of mega-corporations to buy their objects. Libraries are good. This is a tautological truth, a truth that perhaps is being eroded away as we sink deeper and deeper into the clutches of capitalist realism. Libraries are places of resistance; an institution where information is free and access to it isn’t predicated upon the mining of your personal information and your browsing history to be bought and sold. In an economic system where all aspects of one’s life are packaged up and sold to be bought by companies so they can sell you more things, the library represents something entirely antithetical and radical. An institution with the capacity for active engagement with the world which encourages its users to be active with it.

After we finish “studying” at the library we walk to Grand Central Terminal to catch the 6 train to the East Village. We visit a speakeasy behind a phone booth in a hot dog shop and enjoy a round of cocktails in our booth. The streets have come alive with people waiting in line to get into the dozens of restaurants tucked into every space; a ramen joint right above a small bistro. We settle on a soup dumpling restaurant without having to wait long for a table and order plate after plate of food. We continue to explore the village and peruse a used bookstore (I don’t have any cash on me despite a rather attractive book by Adorno that is calling my name). With the air still warm, and with a buzzing yet subdued energy in our bodies we enjoy a glass of wine at a bookstore and bar before heading back to Brooklyn.

The subway car and its elongated perspective, ever-changing cast of characters, and bustling atmosphere provide a wondrous subject for drawing. Some people knit, some read, some listen to music and close their eyes, some make conversation with their seat companion, a high number of people just look at their phone which makes my life easier, and some, perhaps unbeknownst to me, draw.

***

We begin the next day early with fresh baked goods, coffee, and tea. We have a long journey ahead of us.

It’s an hour-long ride on the 8th Avenue Express. Our destination: The Met Cloisters. The train is an R46 with orange and yellow seats, fake dark wood paneling, and beige walls. There is something hypnotic about racing at high speed down the express track as stations go by in a blur. There is a train on a separate track that is in tandem with ours for a brief moment, allowing us to glance peripherally toward our neighbors. Appearing as if in a zoetrope, their movement is segmented by the columns of the tunnels until eventually; the short film ends when we dive deeper into the earth to continue our journey.

The Met Cloisters is not a real place. It is a construction of various real elements of medieval art and architecture joined with contemporary architecture to create a simulation of a medieval monastery while also functioning as a museum for artifacts and objects. My drawing of the herbal garden is a geometric exercise in representation and perspective. I wonder if the monks who would have resided in a cloister such as this ever drew the space they lived and meditated in. While originally a cloister would have had glazed windows in the arches, separating the inside from the out, it would have had the most natural light of any part of the monastery.

We leave the Cloisters and walk through Fort Tryon Park to Washington Heights. If my limited ability to translate train operator intercom-speak means anything, the A train to return to Brooklyn is delayed between stations due to track maintenance on 81st Street. The car is warm, there is someone on their phone saying they’ll be late for an appointment, and after about 15 minutes we start moving again. Transferring to the F back to Brooklyn, we walk along 8th Avenue as children head home after school to ask for ice cream from older siblings and nannies. At a Middle Eastern bistro, we sit down for lunch. I draw as we wait for our food.

Prospect Park is Brooklyn’s largest and oldest forest and New York’s second-largest park with 250 acres of woodlands and meadows. I buy a vanilla soft-serve ice cream with a cake cone. Perfect for a warm afternoon. We meander along its paths and come across the boathouse. We buy a bottle of wine and spend the evening at George’s apartment

***

Our final day is a hurrah like no other and to begin, we wake up early to get breakfast from my cousin’s favorite bagel shop. We ride the G train up to Williamsburg and meet George at a deli where I order my much sought-after perfect pastrami on rye with mustard. We eat in the park, a hornet attacks my sandwich, and I drop half on the ground. There is no greater tragedy. I enjoy what I can then discard the remaining dirt-covered half in sadness.

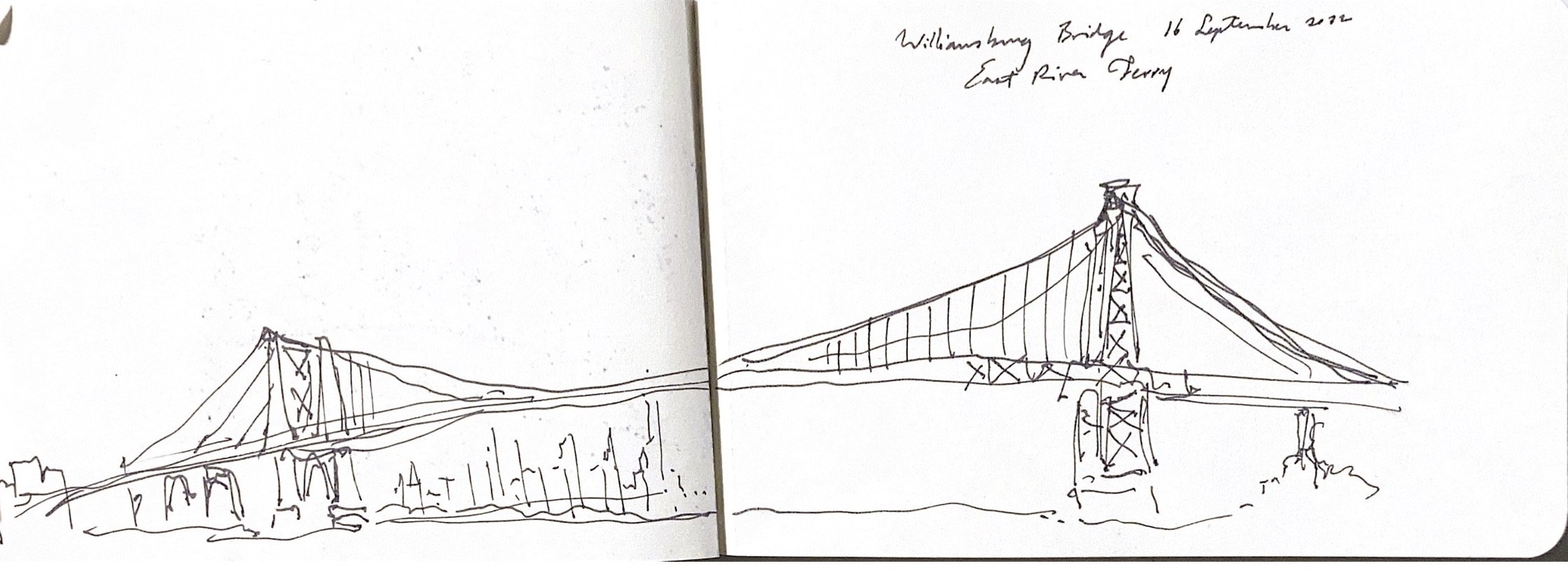

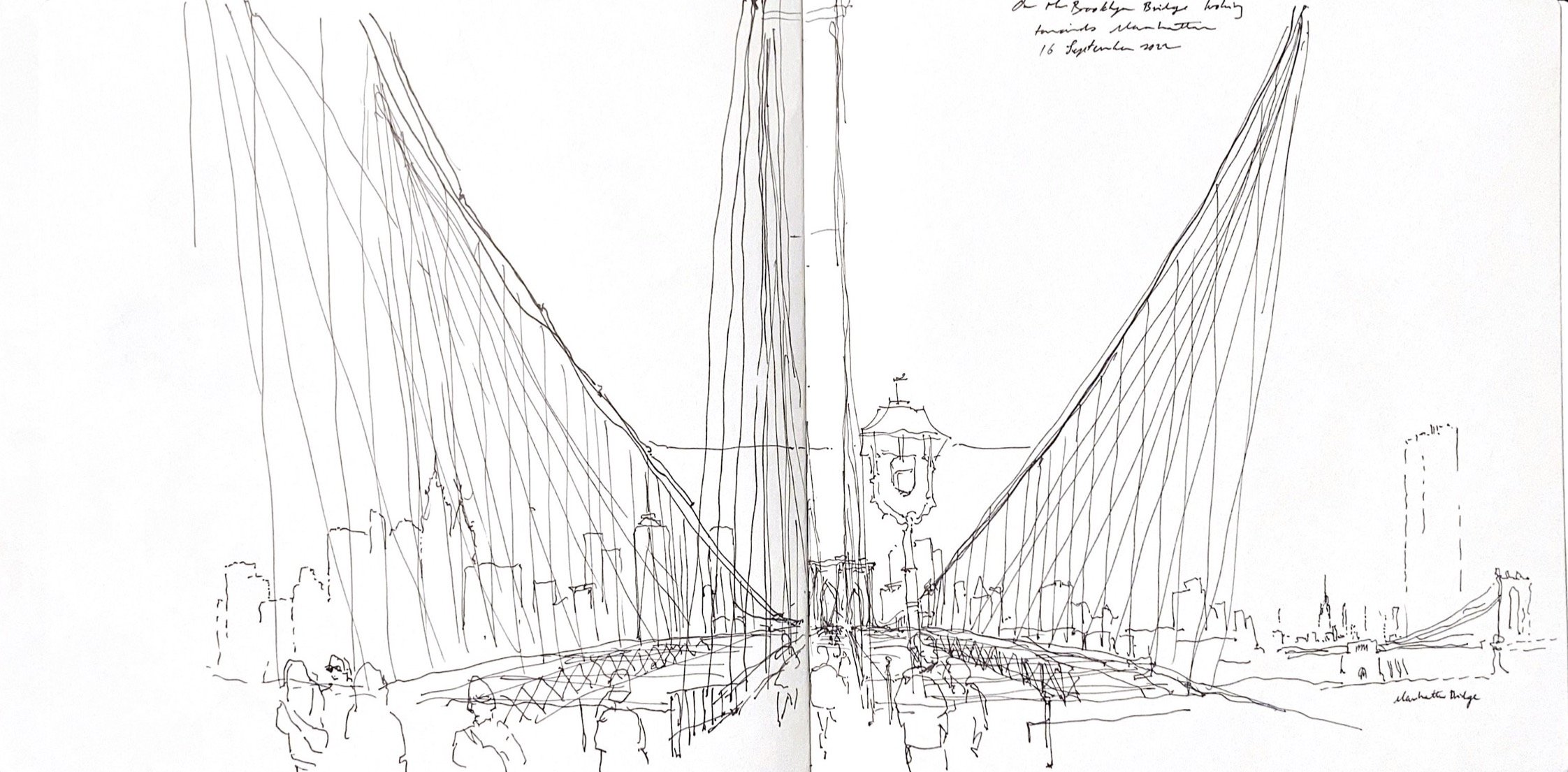

Walking through Williamsburg, we have enough time to kill and on a whim decide to ride the East River ferry to DUMBO. The sky is clear, we pass under both the Manhattan and Brooklyn bridges. When we dock, we make our way to the Brooklyn Bridge to begin the pilgrimage across to Manhattan. It is busy, people are posing, and there are countless vendors selling NYC-themed wares and cold beverages. I pause to draw.

As we continue, Sam grabs my hand to guide me as I walk and draw at the same time. People get up on benches and railings to get the photo. That photo which shows that they came, they saw, and they conquered. They don’t need to look at what’s behind them, they need you to see where they are. This is proof that shows everyone that yes, I made it to this spot.

In Chinatown, we visit what is to become my favorite bookstore of the trip. It is a single room with a small reading nook in the back. There is a bar and counter to one side, with shelves filled with both new and used titles wrapping around the walls. The interior space is warm and cramped and outside it is tucked between a laundromat and a dumpling restaurant. The space used to be a funeral home supply store, a darkly ironic location for a bookstore.

A mix of new and used, Yu and Me Books is centered around Asian American voices. This is a true bookstore, one in which there is a thread of logic connecting each and every one of the titles, an intentionality that does not exist in the Barnes and Nobles of the world. While it is not a store one could get lost in, the spirit of the store pulls one in to engage with it. There is a sincerity and desire to provide a unique voice amidst a growing sea of homogeneity. I hope, of all the places visited on this trip, that this place will be here when I return.

Passing through Chinatown, it feels odd to be in a place that is both a home for so many people as well as a sightseeing stop for thousands more. These are people whose lives have become entangled with the nature of the city as a spectacle, but these are lives, not spectacles to be witnessed.

Crossing Broome Street we enter NoLita, passing countless high-end chic shops and bistros that look too pristine. This area has become curated and preened to such an extent that it is difficult to believe that anyone actually lives here. It is almost too picture-perfect. Is this a performance of the city? Is this the “New York City” that people have come to see? Shops attempting to be “neighborly” and have “history” but are in fact only in their infancy?

Washington Square Park is where our feet finally give out. We plop down on the lawn and rest. There is a jazz trio playing. People are soaking up the warm September day. I am determined to visit another bookstore. Mercer Street Books is unpretentious in its offerings of stacks of books, ephemera, and records. The chaos of the shelves is a curiosity. It is a labyrinthine browsing experience where you are expected to work to find something that you don’t even know exists. There might be a book calling out to you somewhere amongst the piles of $3 paperbacks and 50-cent out-of-print quarterly journals. You just have to listen. A collection of Kandinsky’s essays and a book of architectural drawings are my two finds.

We take a train north to Chelsea to meet my cousin for dinner. We are early and decide to walk to Madison Square Park. Only a few blocks away…from east to west. By this point in the trip, we are stumbling our way from avenue to avenue. The Flatiron and Empire State buildings standing tall above seas of traffic and pedestrians are almost dreamlike. From a bench, we watch running duos chat about their day, people waiting for friends to get off work, dog walkers rushing, business and salespeople finishing up their last calls of the day, and others reading and people-watching.

As we walk back to Chelsea, the sun sinks lower, and Manhattan enters an evening glow as the street lights turn on, and the orange and yellow of restaurants and cafes bask into the blue and purple of the street. At the restaurant, everyone at the table orders the same kind of ramen, it is rich, comforting, and filling.

This gives us just enough energy to get back on the train to Brooklyn. In the dark, the window lights of skyscrapers replace the light of stars. It was difficult to not fall asleep on the train; the city’s cradle rocking us into a slumber to the sound of wheels on tracks.

“The right to the city is not merely a right of access to what already exists, but a right to change it after our heart's desire. We need to be sure we can live with our own creations (a problem for every planner, architect and utopian thinker). But the right to remake ourselves by creating a qualitatively different kind of urban sociality is one of the most precious of all human rights. The sheer pace and chaotic forms of urbanization throughout the world have made it hard to reflect on the nature of this task. We have been made and re-made without knowing exactly why, how, wherefore and to what end. How then, can we better exercise this right to the city?” -David Harvey, “The Right to the City”

Concrete Abstractions

Marx says in the introduction to the Grundrisse:

“The concrete is concrete because it is the concentration of many determinations, hence unity of the diverse. It appears in the process of thinking, therefore, as a process of concentration, as a result not as a point of departure, even though it is the point of departure in reality and hence also the point of departure for observation and conception”.

I liken the act of drawing to this way of thinking. To draw is to concentrate and unify a diverse and infinite number of points and observations. My drawing reinforces my perception of the concrete, and my perception reinforces my drawing. I proceed from my observation to the page, the marks on the page then create a system, which then continues to inform my observation. A dialectic emerges.

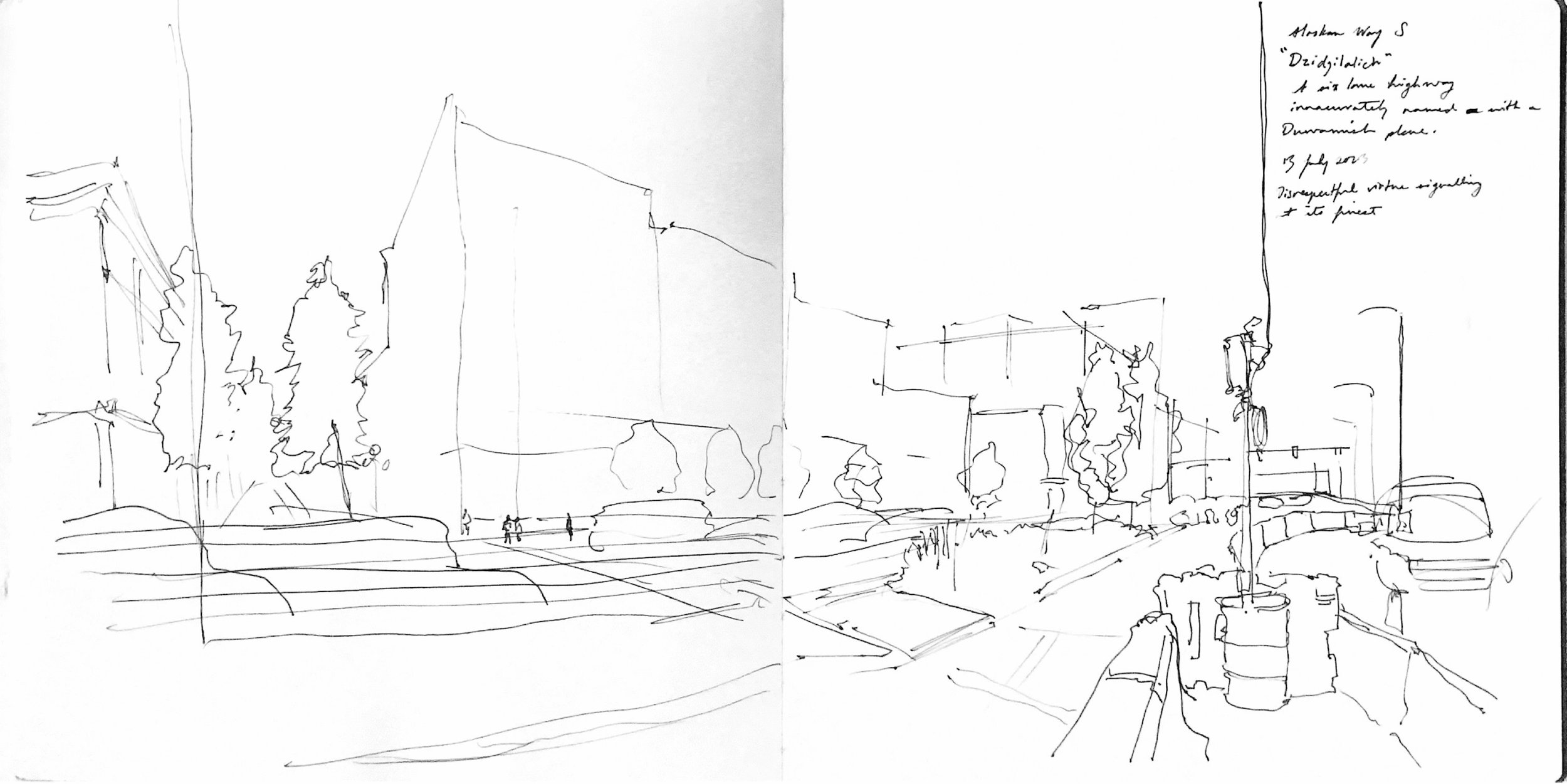

A highway by any other name

Is still a highway. The viaduct has been flattened, not replaced. It exists in a new form. Six lanes of high-speed traffic whooshing by at 50 mph. Hardly a picturesque sight for the waterfront. And to call this eye sore of a road Dzidzilalich is an insult in of itself, but also to the original name of the Duwamish village that once lived here which is correctly written dᶻidᶻəlalič “little crossing over point”.

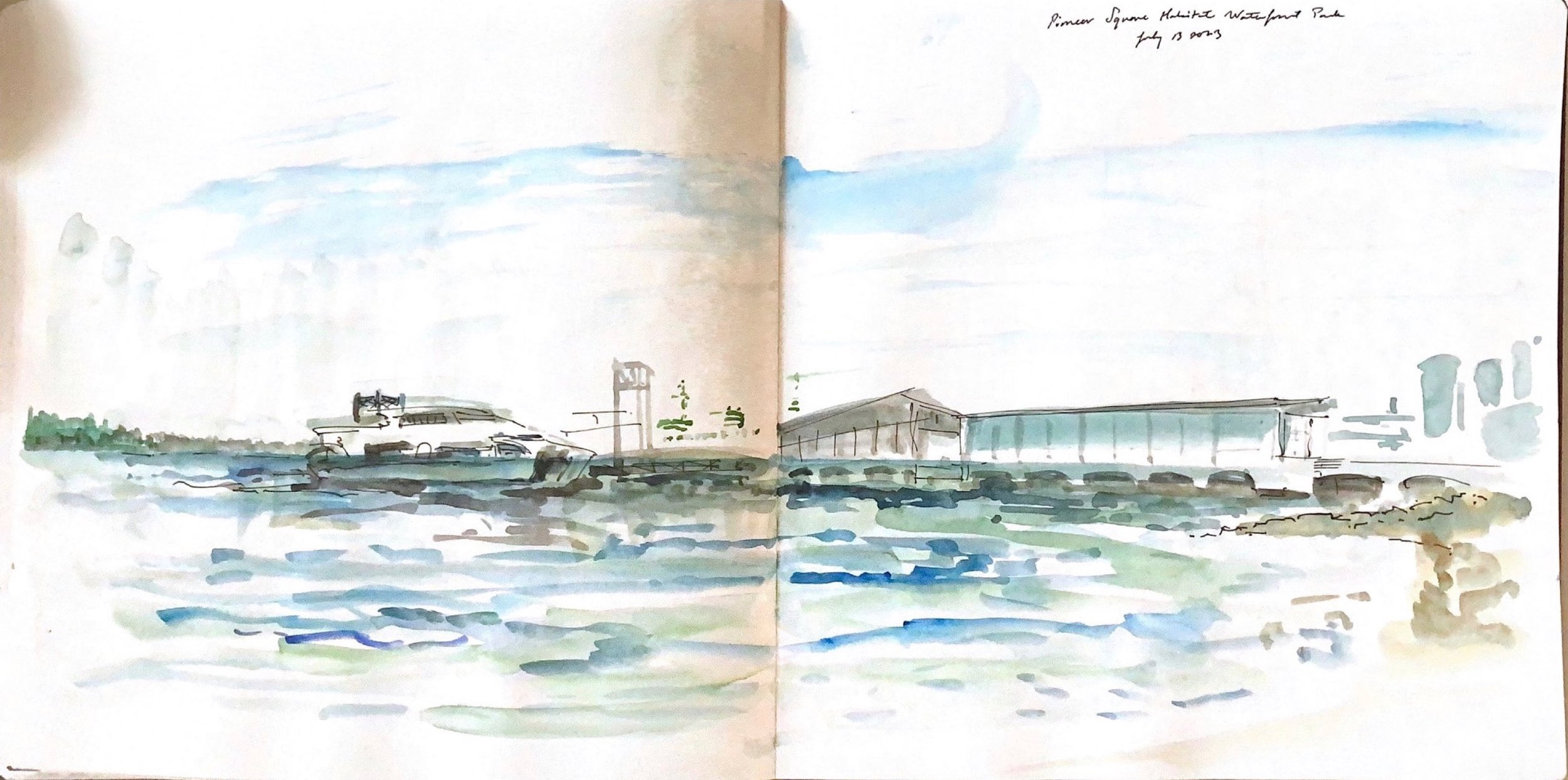

Docking clipper

The water is always what interests me first. The waves will never submit to the eye of the artist. How to capture motion in a single moment? To both imply the moment before and after. The creation of a mark indicates stagnation and permanence. But waves have no permanence. By their very nature, they are swirling, crashing, forming, and refashioning themselves. A docking clipper that takes passengers between downtown and West Seattle pushes water to the shore.

The waves I once saw a pattern in have been subsumed under the wake.

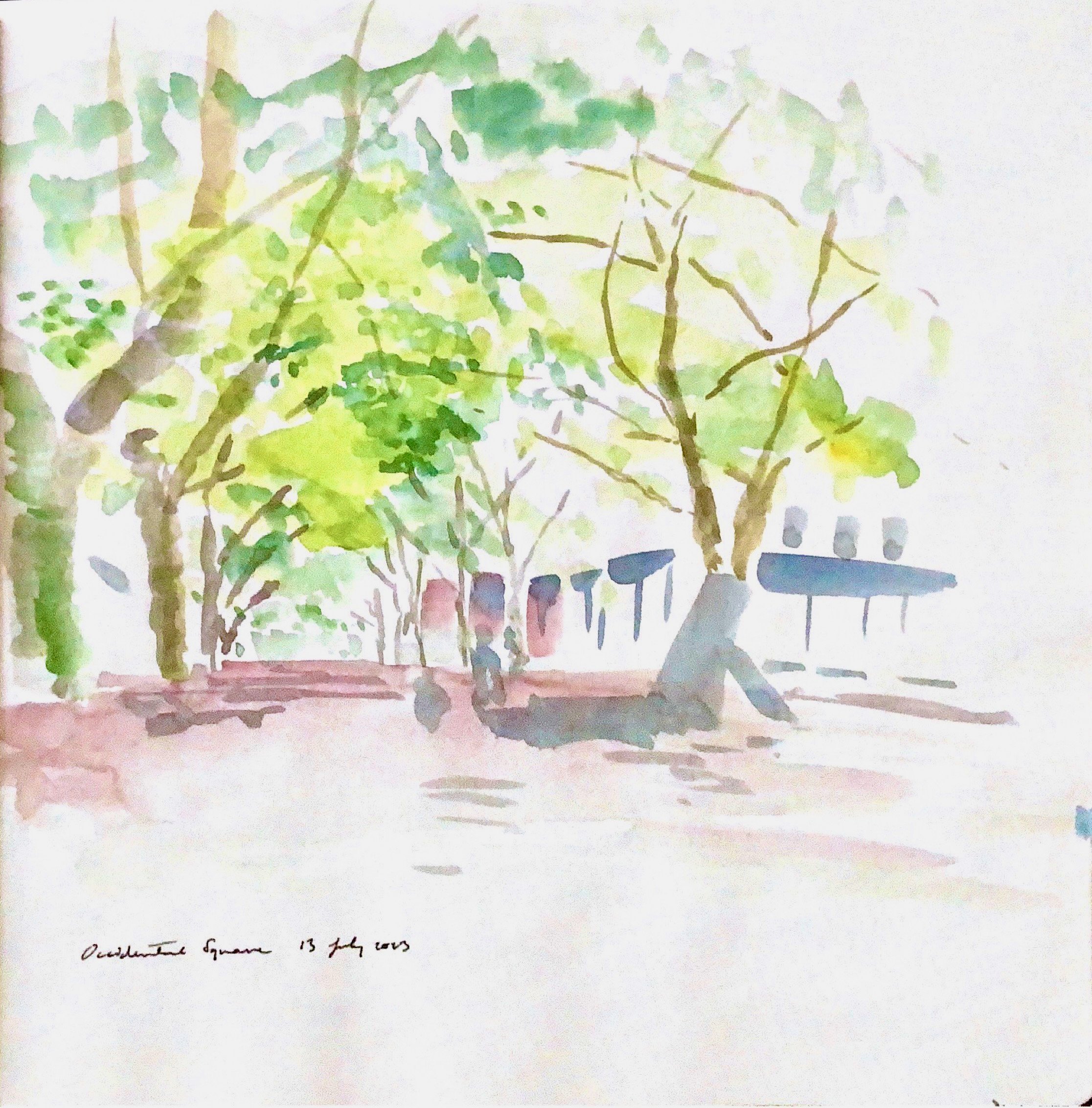

The shade of London Planes

No thought. Just immediate perceptions of color and light. The beauty of watercolor is its blurred instantaneity.

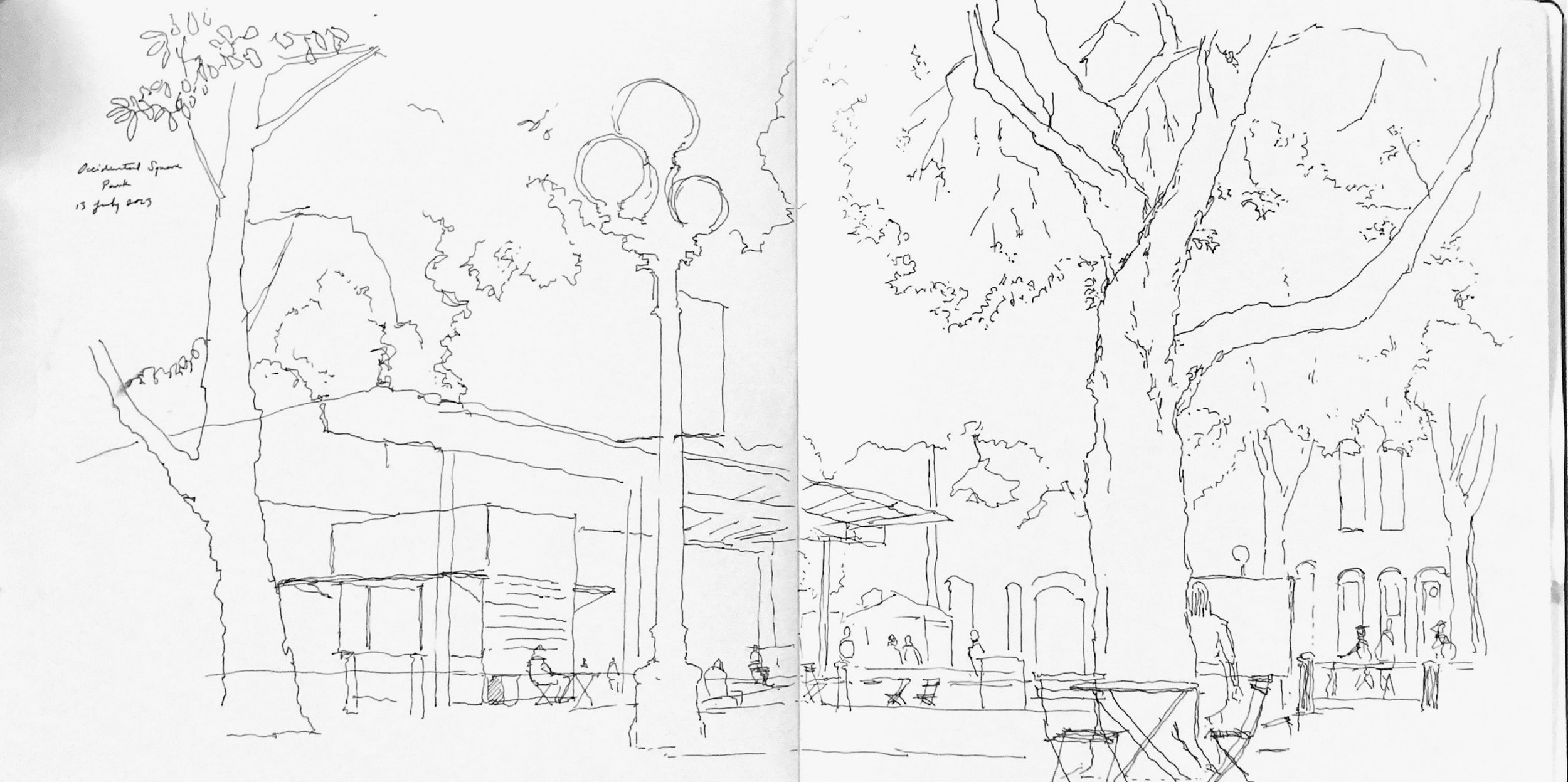

Occidental Square | linear representation

The inventiveness of drawing is in the line. A one-dimensional mark. Having neither breadth nor width, the line exists only in the mind of the viewer. An imposition on reality to make reality more comprehensible.

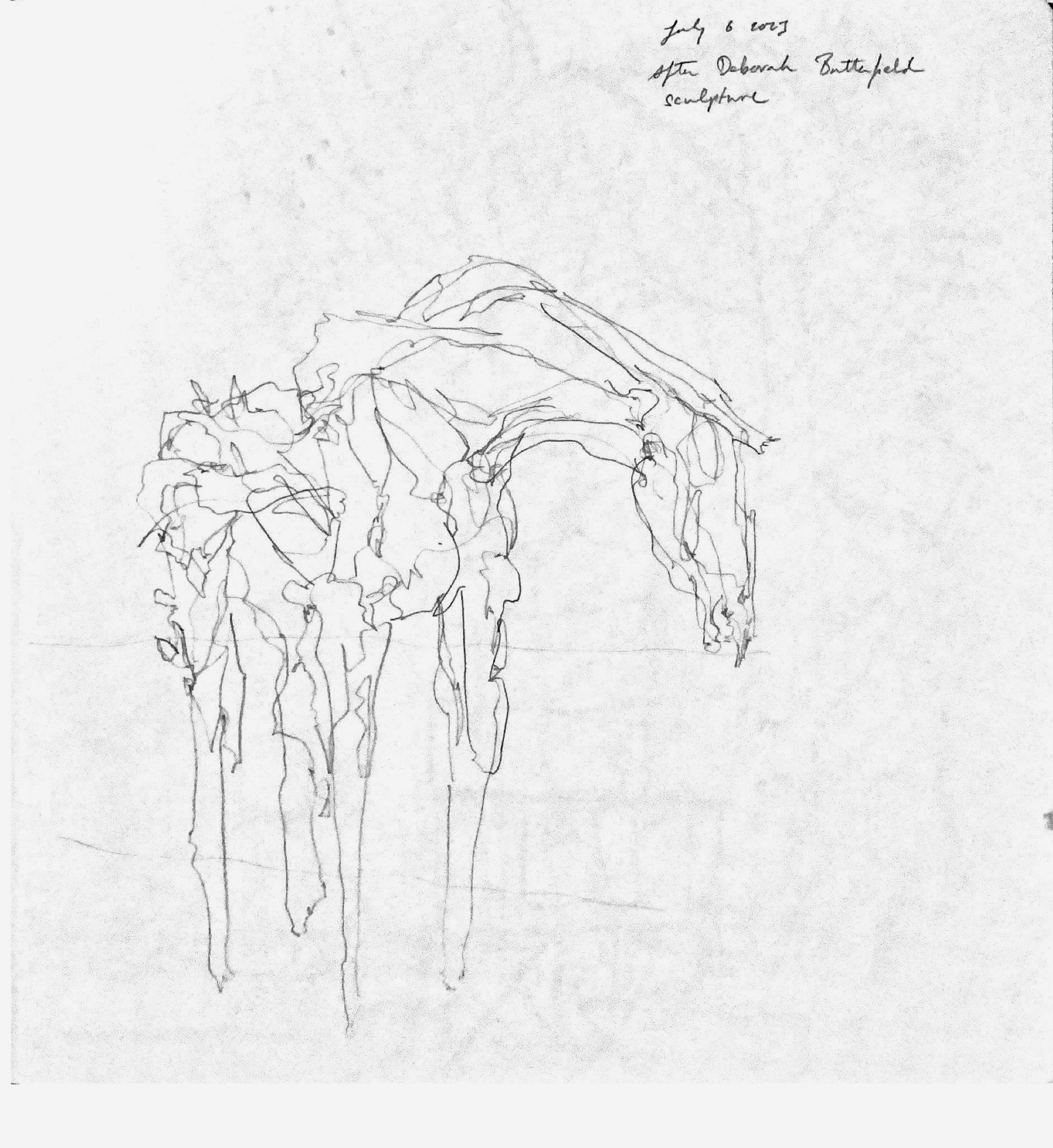

A gesture: Horse, Wood, Bronze

What if a gesture drawing of a horse was cast in bronze, and made to look as if it were made out of reclaimed driftwood? That is what Deborah Butterfield has done. And I reverse the process, moving from sculpture to drawing. Flattening the form. Choosing one out of an infinite number of points of view.

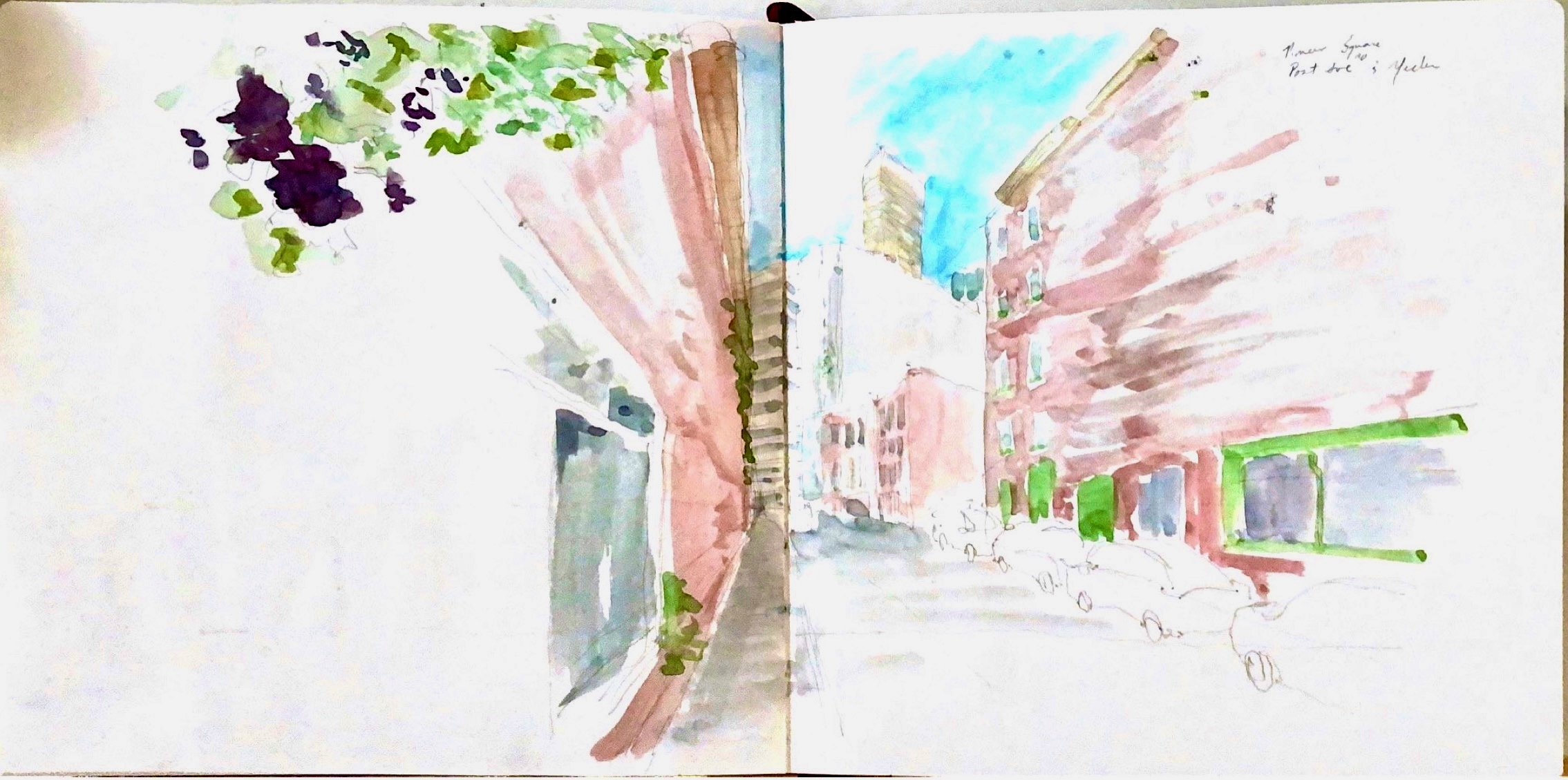

Post Ave and a pocket of sky

Post Ave turns at an angle of approximately 30 degrees to the west as it continues north. Directly behind me, Yesler runs east-west. But the next street to the north, also out of sight, runs northeast-southwest.

Affair Recommendation Parallel Damp Orange

“DEF. 3. By idea, I mean the mental conception which is formed by the mind as a thinking thing. Explanation: I say conception rather than perception because the word perception seems to imply that the mind is passive in respect to the object; whereas conception seems to express an activity of the mind.” -Spinoza, Ethics, On the Nature and Origin of the Mind

Primary colors

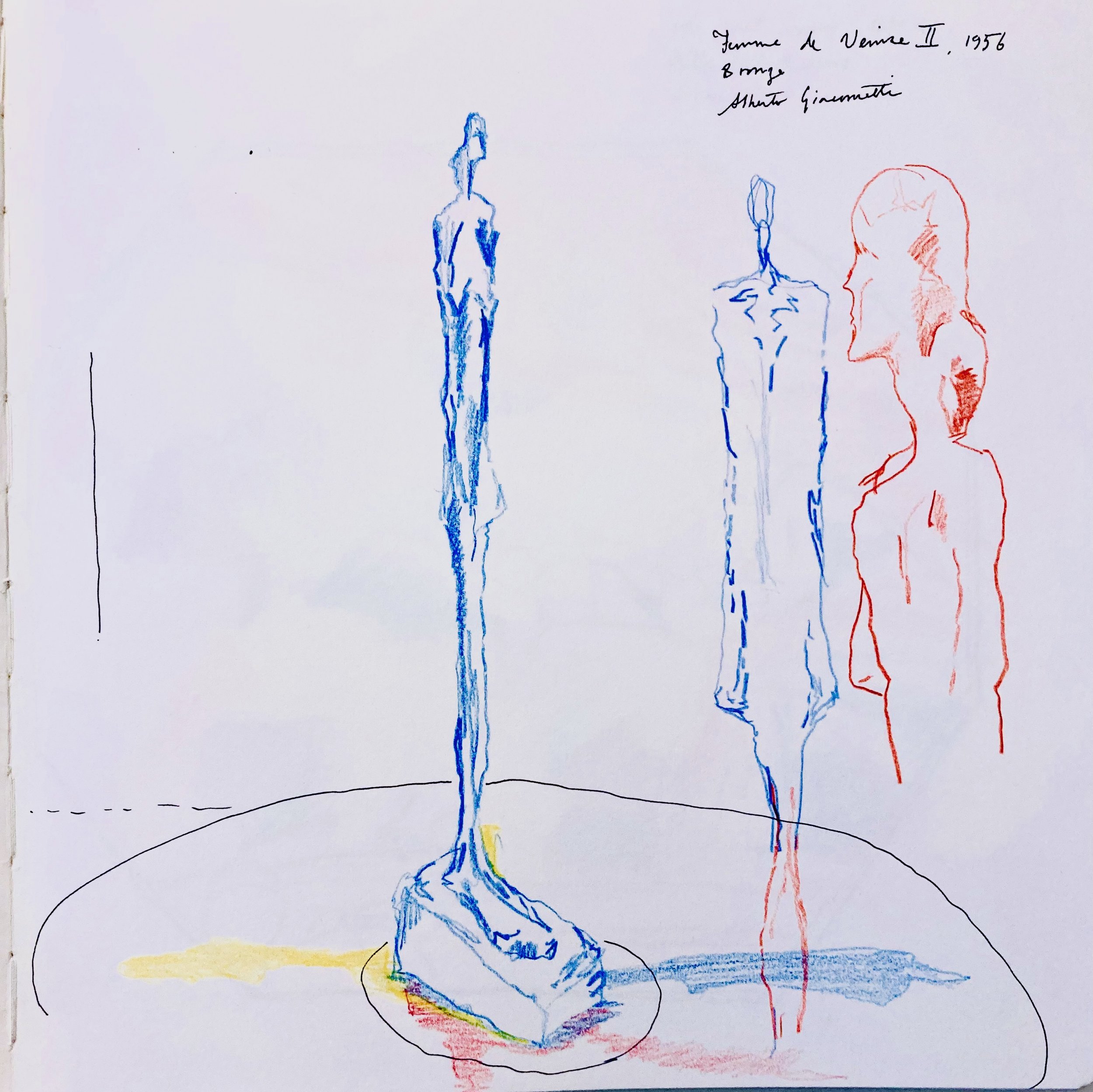

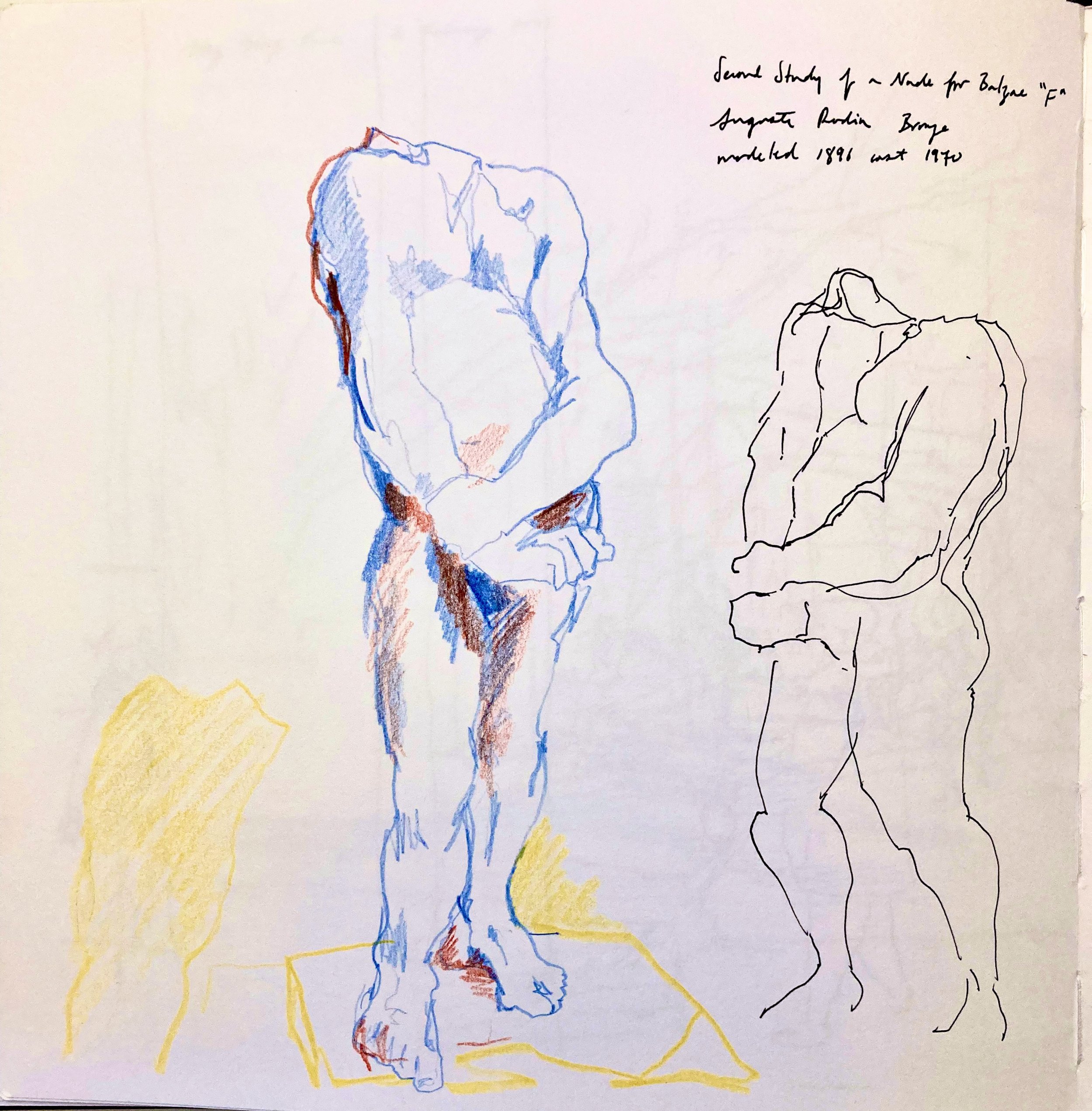

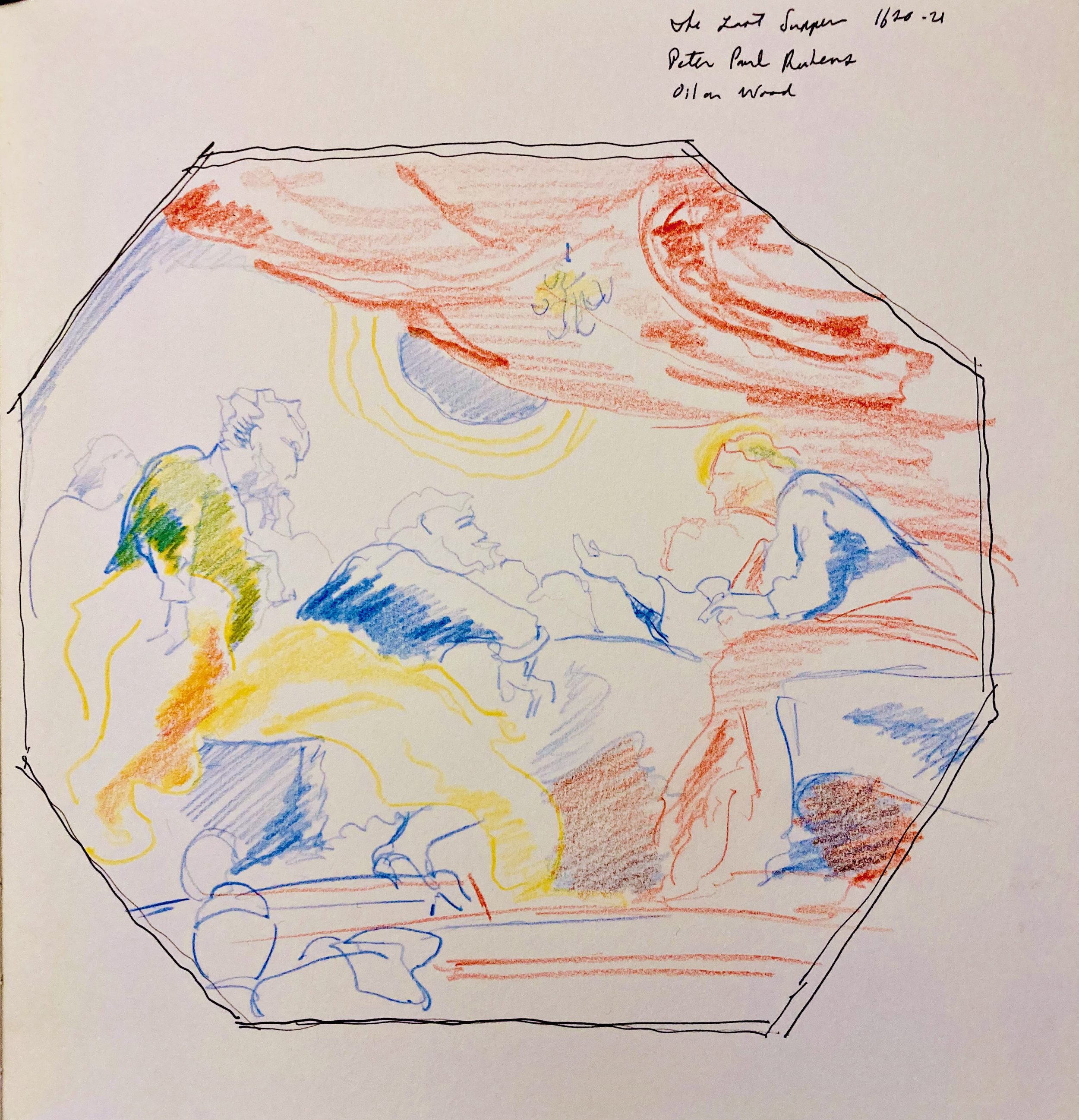

I recently went to the Seattle Art Museum and brought my sketchbook, as I usually do when I go out. But when I was already walking to the train, I realized that I had forgotten to bring a graphite pencil.

Museums are generally very strict about using ink in the galleries, and so I try my best to bring a non-ink drawing implement with me. I tend to complain about the stuffiness of museum policy enforced by stewards and guards who tell visitors to put away their pens prior to entering the museum, only to oblige and concede my position upon entering.

Looking in my bag, I discovered that the only drawing tools I had with me that would be “acceptable” to the museum were three colored pencils: blue. yellow, and red Caran d’Ache. The art store was on the way to the museum, so I figured I could simply buy a cheap pencil, but Sam suggested I should take this as an opportunity to be creative within my subsequent limitations and am happy to say that I am quite satisfied with the results.

Giacometti, Rodin, and Rubens make an appearance in color. Not grounded necessarily in realistic representation, but subjective experience.

”A drawing is an autobiographical record of one’s discovery of an event—seen, remembered, or imagined.” - John Berger, Landscapes

To reduce a form

It is always interesting seeing how one can abstract a subject. The process of simplification perhaps is misleading, because there are many ways to alter, reduce, and change a form so that it communicates a certain meaning. A simple message is not necessarily the most accurate, and an abstracted form is not necessarily the most truthful. Abstraction is more of a lens of focus that can be employed as a tool in order to gain insight into an aspect of the subject. Using distortion and manipulation as tools to bring forth parts that would otherwise be obscured.

In the example below, I abstracted the arrangement of windows that were illuminated on an apartment building in the University District.

“Art does not reproduce the visible but makes visible.”

-Paul Klee

Architecture and Topography

I started this drawing on the corner of 1st ave and University St on the 13th of October 2022. It was hot, stuffy, and smoggy outside. I wore a mask as I stood at my easel set up in front of the hammering man outside the Seattle Art Museum.

The smoke enveloped the surroundings like a curtain, rendering anything beyond a few hundred feet practically unseeable.

After only being able to tolerate this environment a short while, I focused only on drawing what little I could see onto the page, then hastily packed up my things and returned home.

What is the relationship between a city and its topography? What affect do the hills and rivers have on the layout of streets and blocks? What does the sediment type have to say about what holes are dug into the ground, and what steel and glass monoliths are erected on top of it?

How do people perceive the relationship between the buildings we inhabit and the land? How is a city changed by the topography and how is the land changed by a city?

Counterpoint Drawing: A Demonstration

Feel free to put on the music of your choice while you watch. I believe I was listening to Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier as I was drawing. Or perhaps view it with the sounds of whatever is in your environment; the dishwasher running, cars and trucks passing on the street, your upstairs neighbor pacing back and forth.

Musical counterpoint in two-handed drawing

Topographical drawing resulting from abstract two-handed drawing. Human-made structures are drawn in tandem with flattened hills, mountains, and peaks. My right-handed holds a brush pen to create the outline of buildings, walls, and pathways. In my left hand, is a blue felt-tipped pen that draws the changes in elevation.

Two separate ideas. Yet originating from the same theme. A conversation between two subjects, or the artist talking with themself?

The process is akin to playing piano. Each hand is acting independently, but they are aware of each other, taking cues from one another, it is a drawing process that Bach would appreciate. Two voices creating harmony of their own volition. One line (on the page or in music) doesn’t simply “support” the other. There is no accompaniment in the usual sense. It is visual counterpoint. A fugue made into a drawing exercise.

But there is also an improvisatory element to this process. There is an excitement in not knowing where the composition will go yet having an almost instinctual ability to find a logical path to the conclusion. A Fantasia in blue and black ink (b-flat minor). An idea is developed over the surface of the paper, one hand creates a visual subject, and the other line imitates or responds. The truth of the work comes from the process; it lives fully in the moment of its creation. Similarly, music and sound only exist in their instantaneous perception and fading.

What I have presented are only the remnants of my experimentation and not the actual process itself. A better representation of this work would be to record the act of drawing and then have it disappear from view upon completion. However, I’m not seeking to translate music into a drawing, merely adopting certain aspects into the practice.

The process of drawing differently is the focus of inquiry, not the final composition. While the resulting abstract forms of line may be fascinating, it is more so the physical, mental, and emotional act of drawing that I wish to investigate further.

When does a drawing begin?

There are some buildings that scream to be drawn. Buildings, structures, views, and environments that say, “I must be drawn.” They shake to get your attention, catch your eye, and urge you to get their form in ink on paper. These structures which you have never seen before, or the likes of which you’ll never see again, or the same way in a specific moment because you’ve had a wonderful lunch, or the weather is just right, so you must commit them to memory not just in your mind, but also in your sketchbook. There’s a permanence to a finished drawing.

There are also things that do not scream loudly. Alleys, objects, houses, and structures patiently wait for the trained and subtle eye to notice them. They do not vie for your attention.

I zig-zag my way towards a view. I don’t walk towards something I wish to draw, plant my feet in the ground, and then start. No. What I’m about to put to paper is a three-dimensional being. Something with an infinite number of viewing points. I can’t just approach something say to myself, “Yes, I am going to draw now” and then begin.

Drawing begins before you put your pen to paper, even before you’ve taken your sketchbook out of your bag. A drawing begins the moment you step out the door.

Deconstructing a Drawing

I begin by establishing my eye level in relation to the scene I am drawing. This horizontal line will span the entire scene, and is nothing more than an abstract projection. This primary line will serve as a sort of foundation for the rest of the drawing.

If we define a vanishing point as the imaginary convergence of a set of parallel lines that are oblique or perpendicular to the picture plane, we will see that the intersection of the purple and yellow lines do not create a vanishing point.

Because the vertical lines in this drawing are parallel to the picture plane, in our construction, they will never converge. In physical reality we know that sets of parallel lines in fact never converge, but the decision to have some sets of parallel lines converge at vanishing points is what determines the type of perspective.

Had I chosen to have the vertical parallel lines in the drawing converge at an imaginary point above the drawing, it would result in a three point perspective drawing.What is occuring with the intersection of the yellow and purple lines is simply where the corner of the structure falls in relation to the eye level of the viewer. Most of the structure rises above, while a small portion is situated below. Within the drawing, this could also be considered a center of vision.

The center of my cone of vision where things are the least distorted by the flattening of the drawing.The number of vanishing points increases with the number of oblique planes in relation to the viewer. X point linear perspective simply refers to the number of dimensions we chose to distort (in our case a maximum of 3). 1 point linear perspective implies one dimension that is distorted while vertical and all other horizontal dimensions remain parallel and undistorted, and so on, and so forth.

I’ve highlighted the “key lines” that inform the construction of this particular drawing. I hope to repeat this exercise and go into more detail in future posts.

Adolphe Charles Marais Peasant Girl with Cattle 1890

Peasant Girl with Cattle, 1890

To draw after another painter. A drawing done after artist X’s “Artwork Y.” To render, in a different medium, the work of another artist. The act of copying, no; imitating, not quite; studying, perhaps. Is this a new piece of art? Or do I owe every line to the artist who created the thing before me? Are my sketches nothing more than a catalogue of buildings, streets, and sidewalks only made possible by the hundreds of architects, city planners, construction workers, and laborers who actually made what I am merely perceiving?

All my drawings are after another person’s labor. The nature of drawing from direct observation is to come after.

The Coast

A series of three watercolor studies.

There is no line between sky and water. The clouds and the ocean never touch, but they are part of the same cycle. The water in the ocean eventually form clouds, and the clouds eventually form water. In an image the rain would cover the whole painting like an overlay. The rain would connect these two separate entities as it does in reality.

(Razor) Clamming

Small mountains of sand punctuate the shore. The tide will slowly wash away all trace of the harvest.

A clam hunter leans on their shovel as they reach into the murky depths of sand and water in search of the coveted mollusk. Their companion watches for the next wave; that surge of water, salt, and sand that will render their work fruitless. The sandpipers look on tauntingly.

Gulls, crows, and sandpipers scavenge from the holes of failed attempts dotted along the beach. It’s difficult to tell the difference between the signs of a clam and a shrimp. Clams are adept at digging and propelling themselves into the sand. The shrimp simply float their way to the surface as if to taunt and discourage the clammer. The birds ate well.

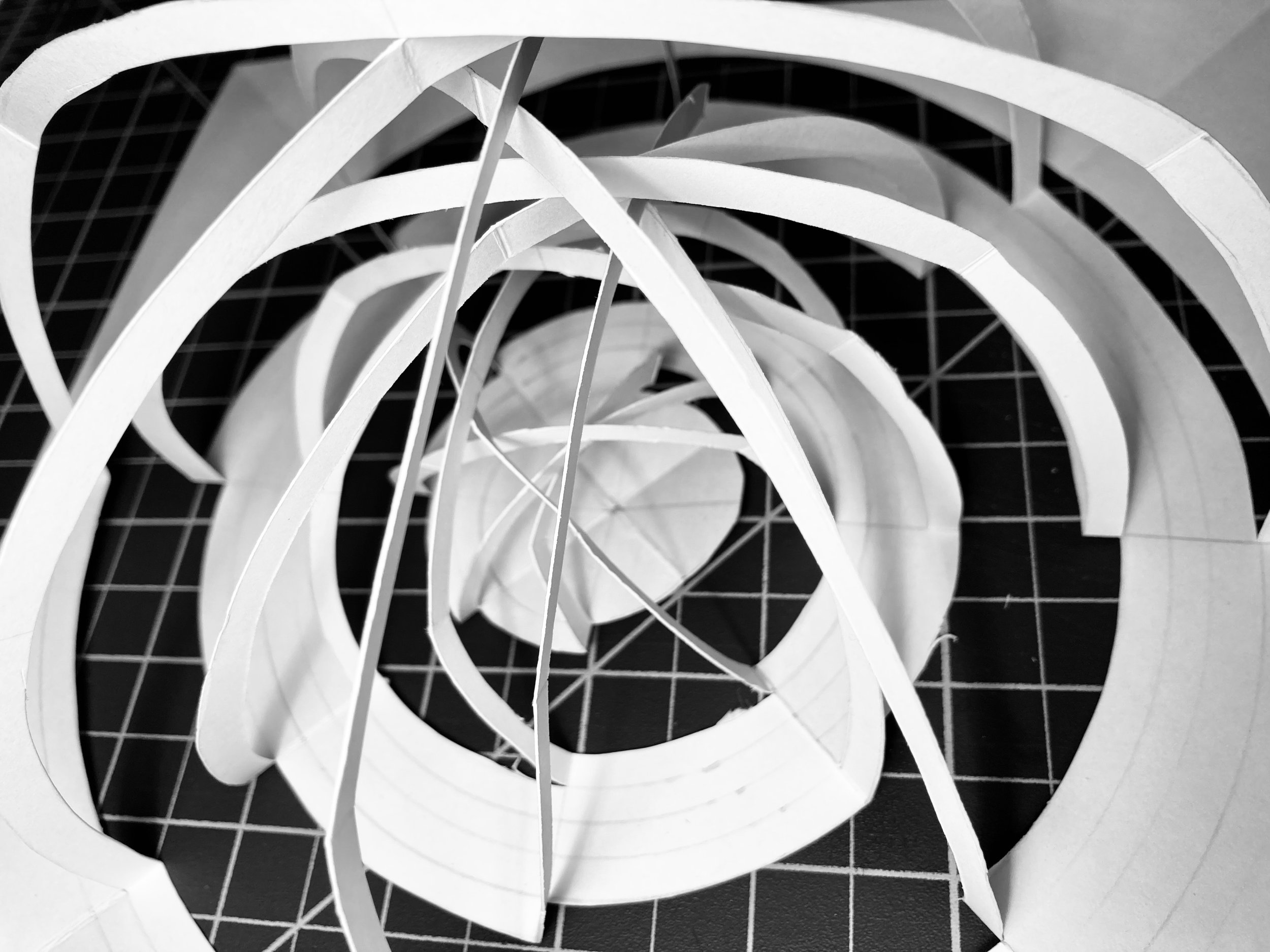

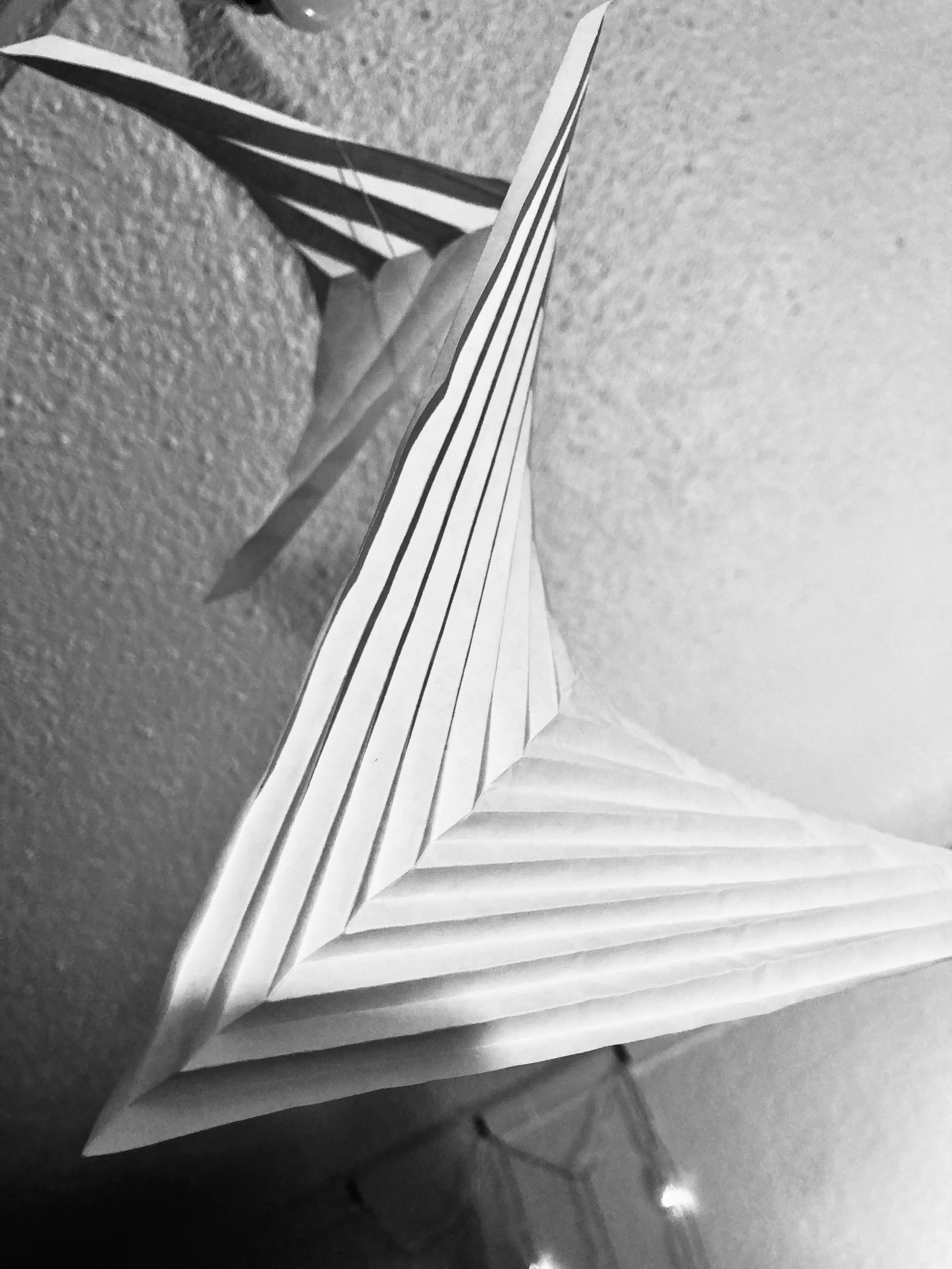

Experiments in Rhizomatic Folding

As I continue to be fascinated by the qualities of paper and its ability to be manipulated and transformed, I want to share this recent experiment that sits on my desk alongside other various projects. Pinching the center of a sheet of tracing paper, and crumpling it, I was able to create a sort of rudimentary cone of sorts. From this shape, I carefully unfolded it and began making creases starting from the center pinch point.

The creases I formed seemed to naturally create a circular spiral without much direction or exertion of will on my part. The resulting effect was rather interesting and by the time I made it to the edge of the page, I had created a wonderful sculpture. It holds its shape very well and is quite springy in response to pressure and outside force.

I am sure there is a mathematical explanation for the reason that the creases form a spiral without little outside influence. But what fascinates me more is the interaction between the seemingly chaotic nature of crumpling paper and the emerging forms that are incredibly ordered and seem to have some underlying principle and set of rules.

The sculpture’s interaction with light is another aspect of this exercise I find interesting. The small slivers of shadows and highlights created by the random crumples and creases are hypnotic; alongside the tactile experience of the lightweight yet durable paper.

The creases are like steep crags jutting out from the earth where two plates are crashing against one another. They remind me of certain peaks in the North Cascades or the Alps.

Simple Thoughts

I’m making embossing lines in paper to help me fold a complex pattern. The ruler is a little wavy. There are 24 vertical lines and 96 diagonal lines. There is a tense feeling in my left elbow from keeping the ruler in place. I’m listening to John Berger talk about writing, life, art, and philosophy.

Berger is calm and thoughtful. He doesn’t hesitate to hesitate. He pauses, sighs, and speaks with a degree of unmatched humbleness.

This is what I do at 11:19 p.m. on a Sunday.

The pre-folding is finally done. I’m not keeping track of time, of how long it's taken me to make this pattern, but my best guess is that it’s taken 27 minutes.

Time to actually fold.

I’ve been folding for an hour now. I’m nearly done with the pattern.

The folds get easier as I go on. The final row of folds fall into place with ease. It is surprising how a series of diagonal and vertical folds produces a curve. The paper seems to naturally curve smoothly on its own. An interesting manipulation and even curiouser effects. I’m sure a mathematician could explain it, but I was never good at math other than logic and basic geometry.

I crumple tracing paper into a ball, take it apart then recrumple it as tight as I can. I carefully unfold it then recrumple it a final time. I’ve made a web of folds. Each intersecting with each other in a complex network of tiny valleys and mountains. When I create strong ribs by creasing the paper, it naturally curves without me even attempting anything.

I repeat my creasing and the paper becomes curved and I create a spiral. Why does it do this?

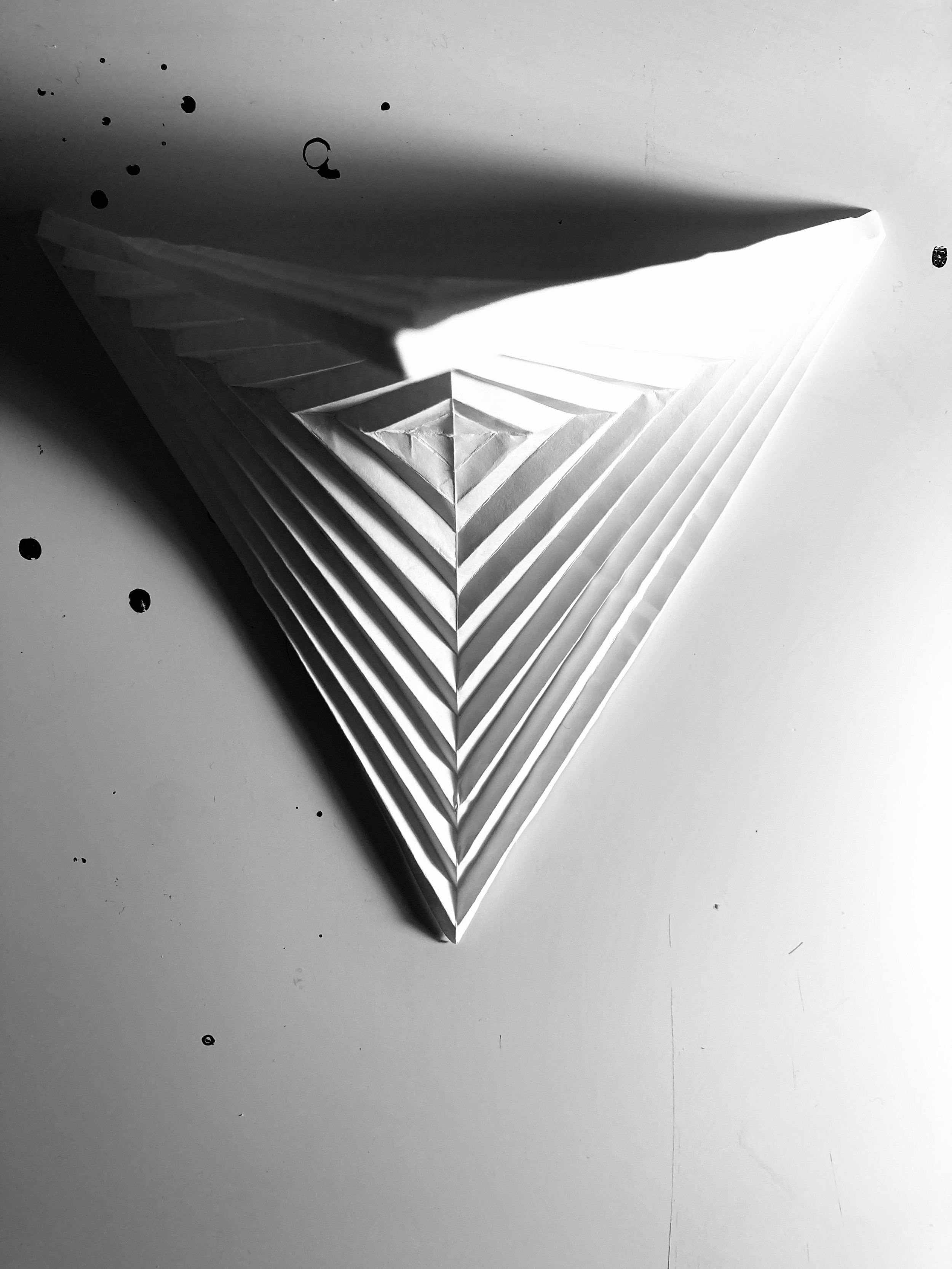

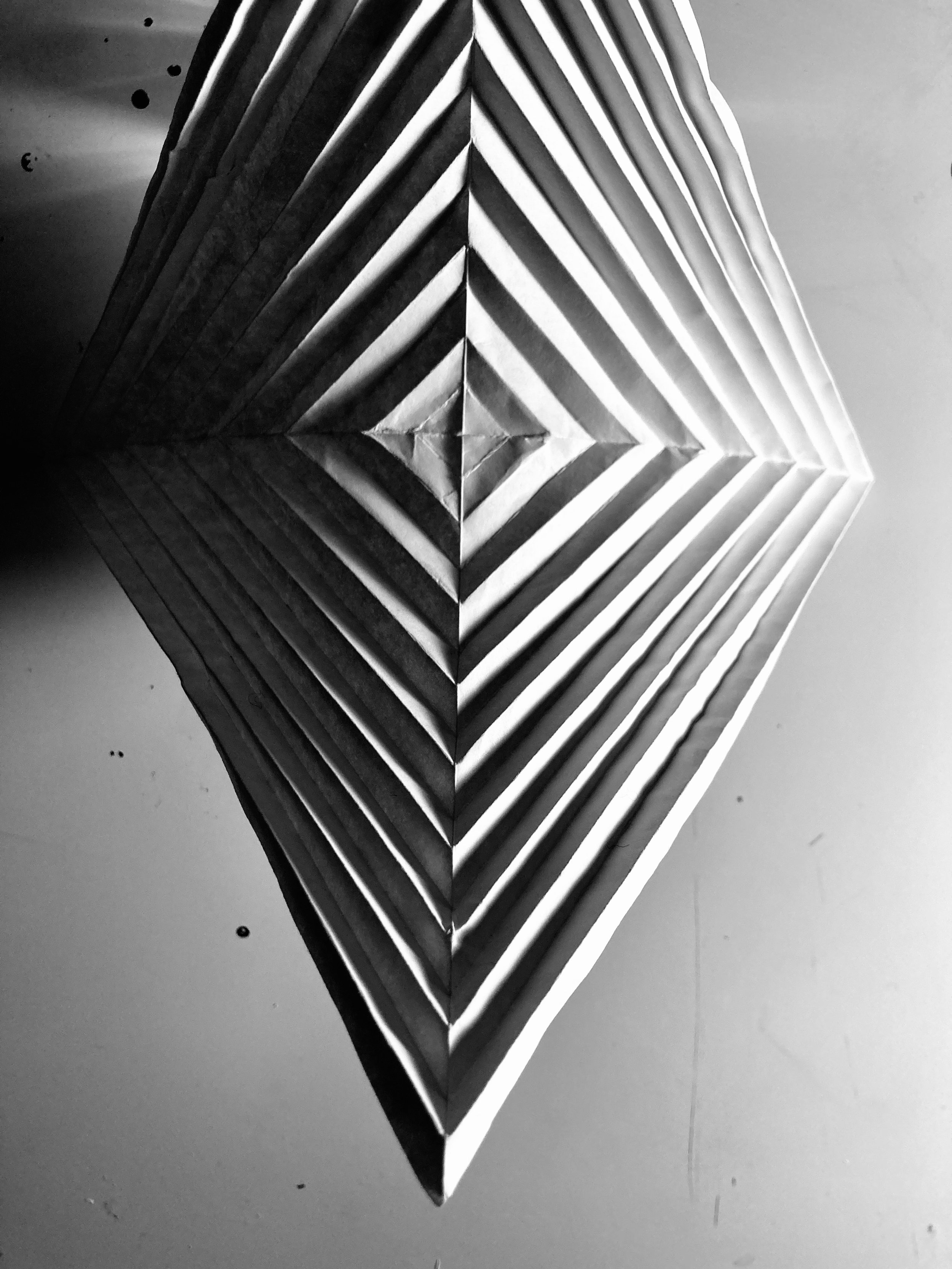

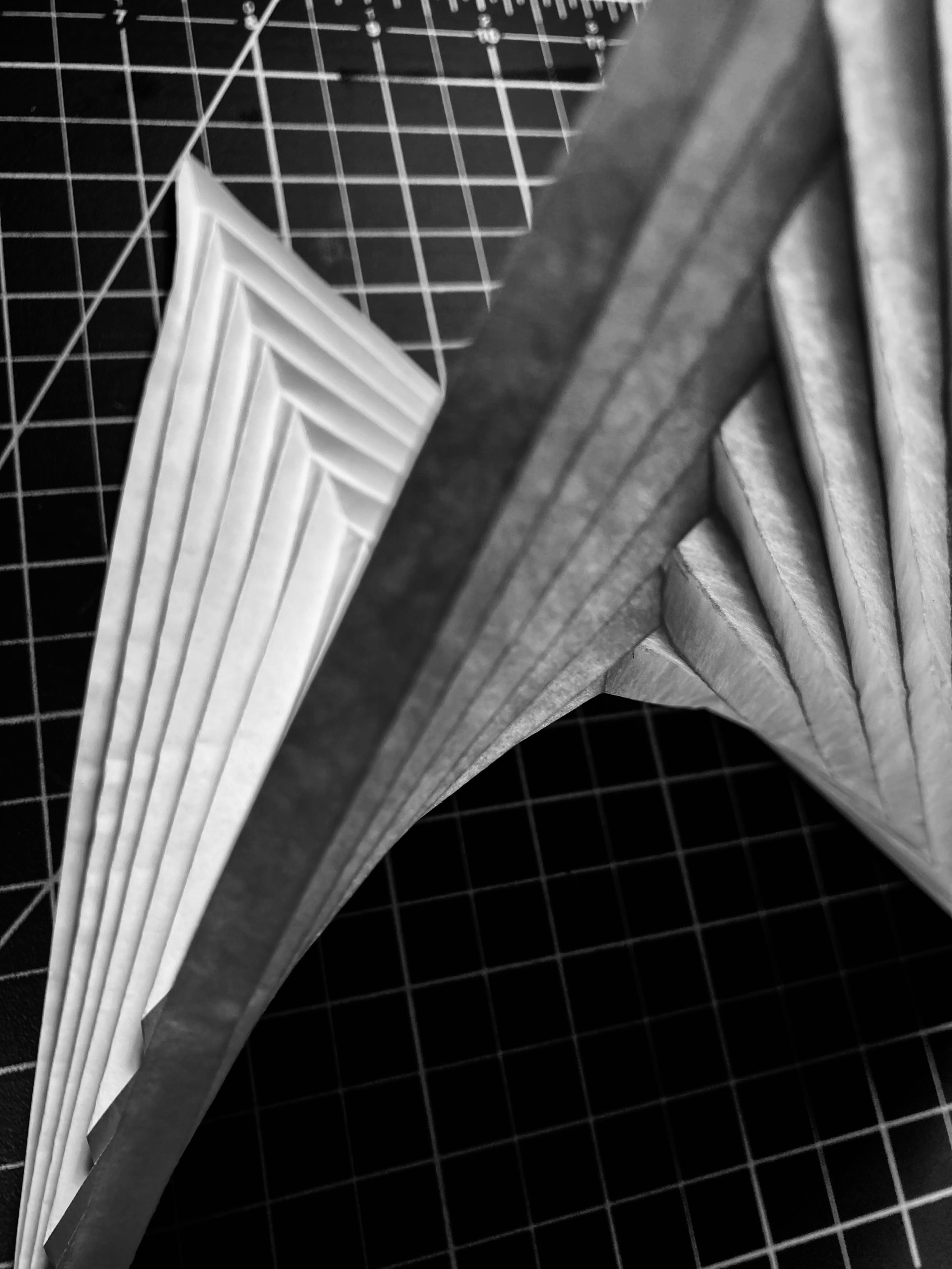

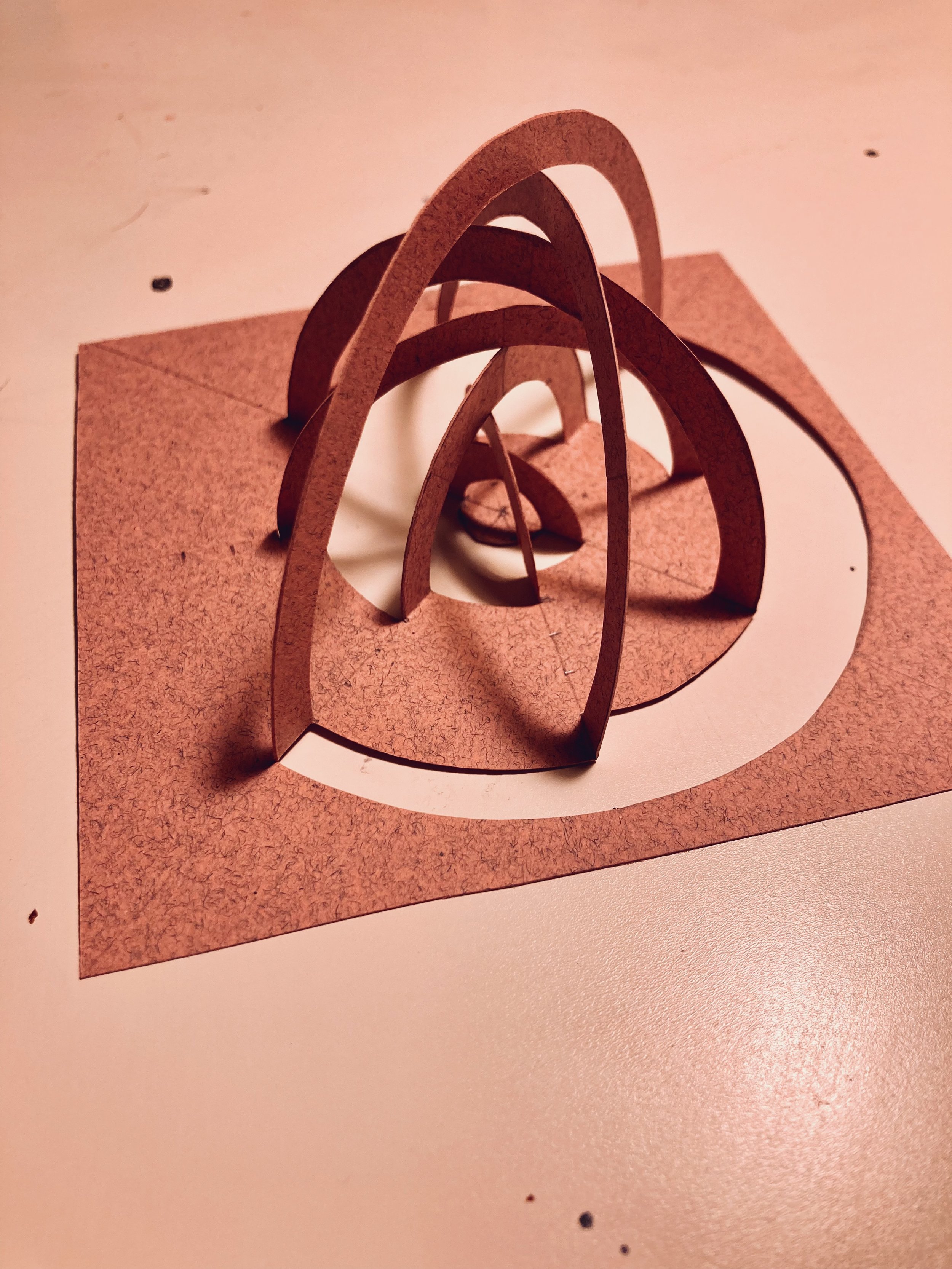

Paper Experiments Part II

Continuing from where I left off, I decided to try something more ambitious. Using multiple reference photos I was able to figure out the basic pattern of this complex looking tower sculpture. I made a small mock up of the template and once I was happy with how it turned out, I modified it by making the struts skinnier so the pattern could be multiplied to a higher degree.

The basic pattern of the tower structure. The upper half is simply the bottom design in reverse.

The final tower design is quite large and measures 12 inches high. I used 300 g/m hot press watercolor paper so it wouldn’t buckle under it’s own weight.

This next sculpture is a simplified version of the spiral design in my last post. Using a smaller piece of paper I applied the same principle of concentric half-circles rotated at 45-degree intervals. With only seven struts, the structure is not nearly as complex, but the effect is much more satisfying. The circles are even able to support themselves when the sculpture is tilted on its side.

This next design was produced entirely by folding.

Another variation on rotating concentric circles; instead of half circles, whole circles are rotated 45 degrees and "hinged” at equilateral points on their circumference. Essentially a paper gyroscope, this design reminds me of medieval models of the universe.

And last but not least, there’s this sculpture that also plays with concentric circles and 90 degree angles. It’s simple to construct and interesting to look at. It took me a minute to figure out how it was made but as with most of the other sculptures, the underlying pattern is relatively basic and the complexity is derived from the use of repetition and transformation.

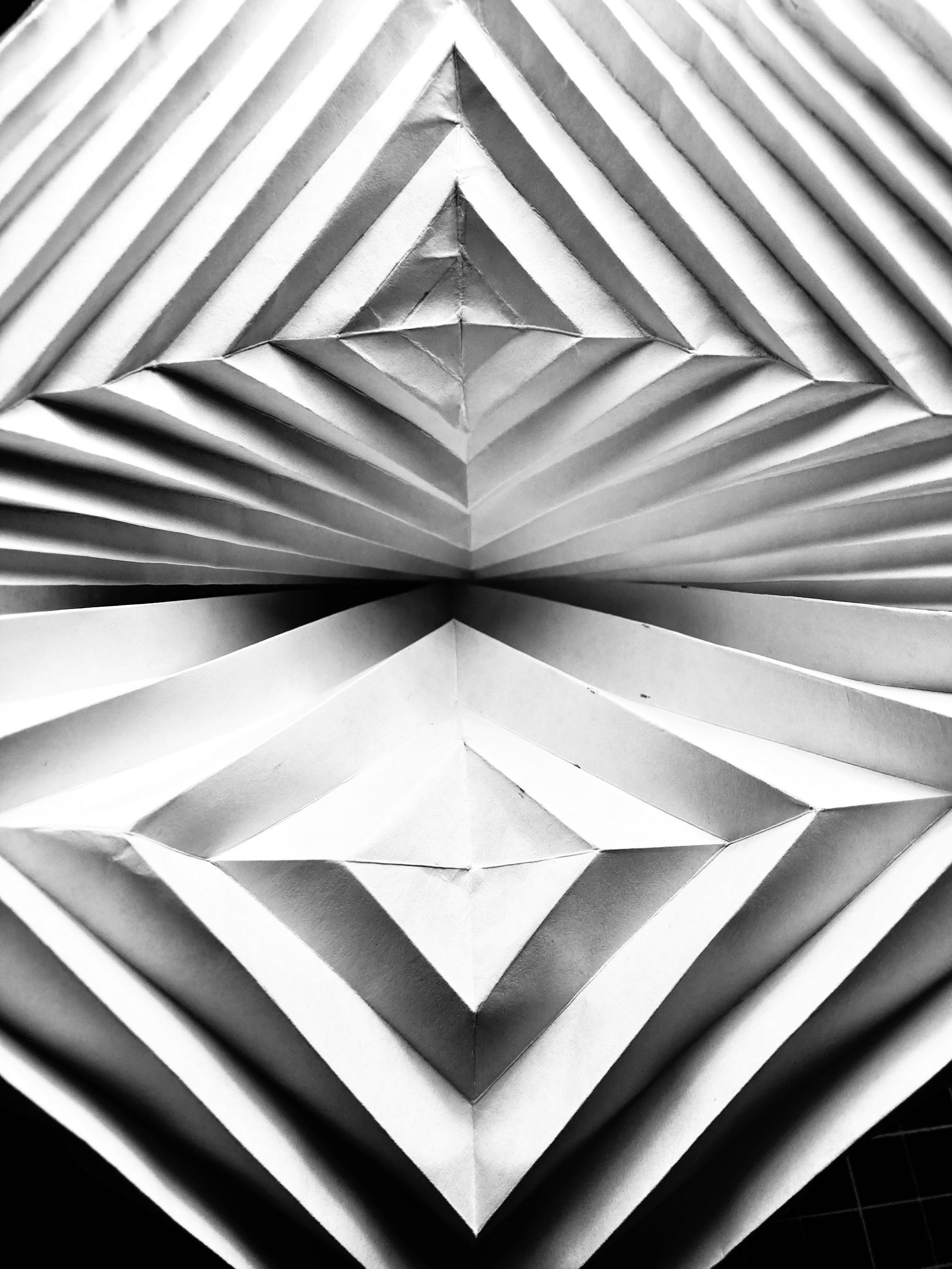

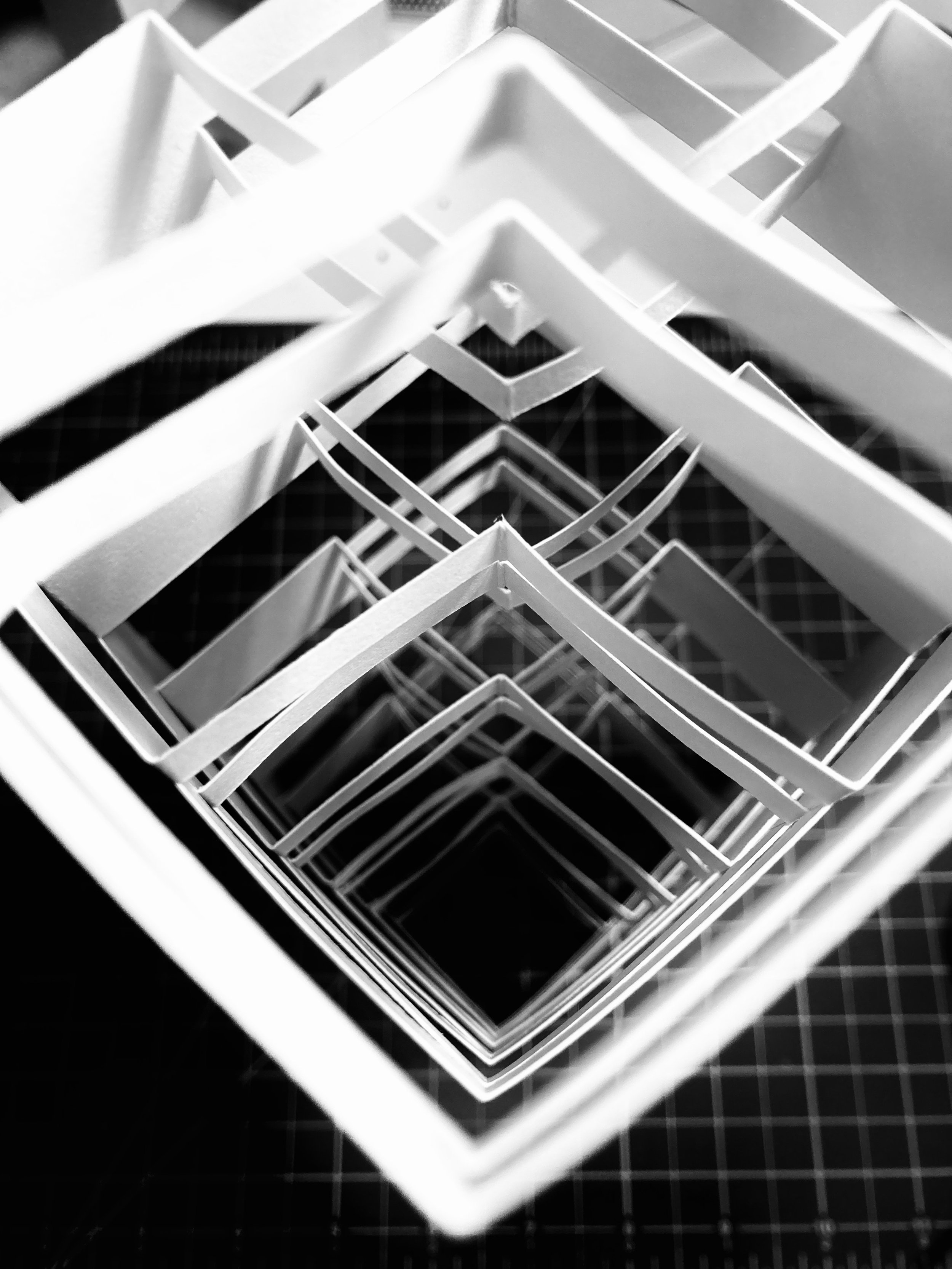

Paper Experiments Part I

If you don’t know me, I am a sucker for anything Bauhaus-related. In particular, I am fascinated by the work of Josef Albers and the various exercises and studies he had his students partake in.

One of those experiments, was to create paper sculptures with little to no waste, using a combination of folding and incisions to produce an interesting effect.

Using various reference photos and tutorials, I was able to make a few of my own paper sculptures that have now taken over the apartment. I find their effect quite satisfying and intriguing, I hope you enjoy.

The first model consists of a series of concentric half squares. Each half is rotated 90 degrees starting from the center outwards, then folded so that each half interesects at the middle. This model is relatively simple to construct. My interest had only just been piqued.

The second model takes the same principle as the first but modifies it so that instead of rotating each concentric half-circle 90 degrees, it is rotated 45 degrees for a more complex sculpture.

The third sculpture is produced entirely by folding.

By taking a square piece of paper, and creating a series of concentric mountain and valley folds, a parabolic curve emerges when viewed from the side. The accordion folds also allow this sculpture to be reversible by twisting each corner gently in opposite directions.

To be better appreciated, I hung two of these sculptures from the ceiling like mobiles.

Stay tuned for part II…

Returning to Urban Sketching

I haven’t drawn on location with a serious mindset in two years. I’ve been spending most of my time drawing from either reference photos or my own imagination. I’m not usually one for New Year’s Resolutions but this year, I’m making a concerted effort to draw on location at least three times a week.

I’m using nothing but a fountain pen and a simple Moleskine sketchbook. I’m trying to improve my understanding of perspective, perception, and construction by taking my time in establishing (at the very least) a horizon line, a measuring vertical line, and perspective guiding lines. From there, I build the sketch from the outside-in.

It’s quite satisfying knowing you’ve correctly measured a certain element, or understood the basic geometry/proportion of a structure by reducing it to a simple volume. I wonder if this practice of mental abstraction then slowly building complexity has any philosophical applications.

On a completely unrelated, but not so unrelated note, I’ve been reading more philosophy books. In particular books on aesthetics and art philosophy. If you haven’t read or seen John Berger’s Ways of Seeing I would highly recommend it. It just might be the best and most interesting book on art I’ve ever read.